The Book Isn’t Always Better, Blade Runner Proves It

Blade Runner is better than the original Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? because it allows its themes to grow, instead of being obsessed on.

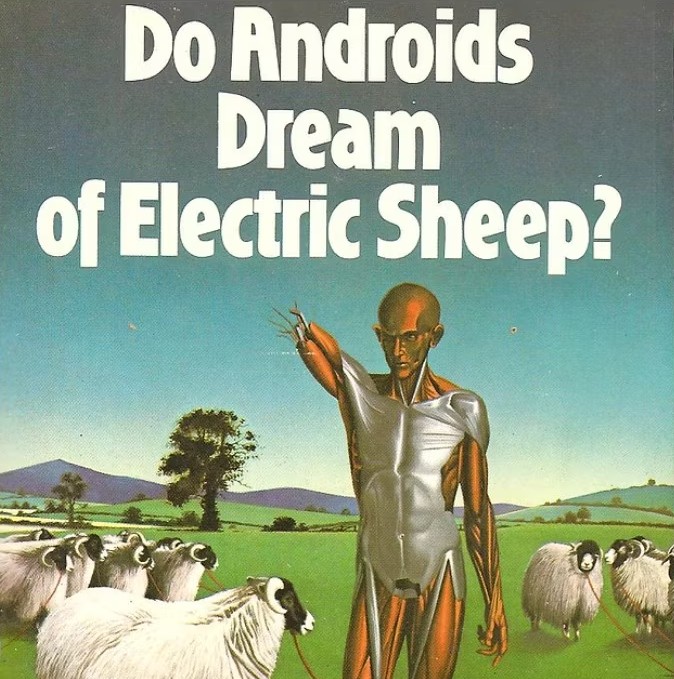

“The book is always better” is a common refrain leaving a theater when one sees a movie based on a novel or a comic or play or pretty much anything. However, while we do not underestimate the power of the written word, one book-to-movie adaptation definitively proves this to be untrue: Blade Runner, the 1982 Ridley Scott science fiction film starring Harrison Ford, based on Philip K. Dick’s 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? While the latter is an interesting, philosophically-driven noir pastiche, the movie adapted from its bones is simply one of the greatest films ever made.

The differences between Blade Runner and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? are numerous, but not to the point of being entirely different stories, as has often happened with Philip K. Dick’s work. Blade Runner at least keeps the central plot of its source material intact; in a dystopian near-future, a Southern Californian bounty hunter tracks down fugitive androids while contemplating the nature of humanity.

This is a far cry from say, Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Total Recall (or worse, its 2012 remake with Colin Farrell), which basically took the idea of Dick’s novella We Can Remember It for You Wholesale and ran with it. At a minimum, it must be acknowledged that movie versions of Dick’s works have much better (and shorter) titles.

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is a very typical Philip K. Dick novel: obsessed with the nature of the real and the artificial (and if there is a difference between the two) and despairing of a desolate world ravaged by mankind’s actions. But it is also a Dick novel in the sense that it is meandering, full of bizarre ideas that go nowhere (like a collective VR religion that may or may not be fake), and frankly, in terms of prose quality, the work of a writer whose only published non-science fiction novel was titled Confessions of a Crap Artist.

The magic of Blade Runner is that it takes the core concepts of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and transforms them from inconclusive musings to enigmatic, emotionally devastating images. It is a truism that art should show its audience what it is trying to convey, rather than tell them, and that is where cinema has an edge over the written word. Where Philip K. Dick got bogged down in his preoccupations to truly focus on what the story could tell, Ridley Scott and Harrison Ford built from them.

All of the changes made from Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? to Blade Runner only increase the power of the narrative, often through omission of explanation rather than clarification. Rather than being set in a nearly deserted San Francisco in a world depopulated and irradiated by “World War Terminus,” Blade Runner takes place in a permanently rainy Los Angeles that is claustrophobic and seemingly overcrowded, even if J.R. Sebastian (William Sanderson) says otherwise. Where the book gave its readers a tired sci-fi trope, the movie simply shows you something about this future is off and wrong, without needing to explain how it got that way.

Similarly, while the idea of the rich owning flesh-and-blood animals as status symbols is blunt in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Blade Runner mostly leaves it in the background, which allows it to reinforce the idea of replicants (called by the much goofier name “andies”) and humans as castes, rather than becoming a major plot point in themselves.

But perhaps most importantly, Blade Runner wholly flips the central idea of empathy that occupies Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and turns it into something more than “humans should care about humans.” The andies of the book are explicitly without empathy; Dick himself said they are “deplorable because they are heartless, they are completely self-centered, they don’t care what happens to other creatures.”

In contrast, the replicants of Blade Runner show more empathy and feeling for their fellow artificial beings and humans than anyone else in the movie, while still being capable of incredible violence and cruelty. While Dick’s novel was obsessed with empathy as an answer, the movie turns the nature of empathy and what it means for humanity into a question. Questions always linger more in the mind than answers, as anyone who has ever read a mystery novel could tell you — or anyone who has ever seen Blade Runner and forgotten exactly what happened in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?