The Ring Was Only Possible Thanks To The Scariest Japanese Horror Film Of All Time

Dread and darkness, intertwined with the human psyche, haunt some films in the labyrinth of horror cinema more than others. None more so than Japan’s excellent 1997’s export, Cure, a monumental horror masterpiece and a gateway to a movement that redefined the genre. Indeed, the film, directed by Kiyoshi Kurosawa (unrelated to the legendary Akira Kurosawa), is a heavyweight cinephiles continue to whisper excitedly about when not debating its depths in academic circles or rewatching it at home.

A Delightful Nightmare

When I first watched the movie—it felt less like a movie and more like a delightful nightmare or a potent drug (or perhaps a nightmare dreamt on drugs). It’s an astonishing and utterly singular work of art.

But what makes the film so extraordinarily provocative and compelling? And why has a contemporary director, a veritable heir to Kurosawa, Ari Aster—beloved for his films like Hereditary and Midsommar—stated that the movie could be the best ever made?

Because Cure is a stirring and unnerving exploration of identity, memory, and the susceptibility of the human mind to suggestion, to the same extent The Ring is a journey into fears of mass media, the abuse of children, and urban legend.

The Story

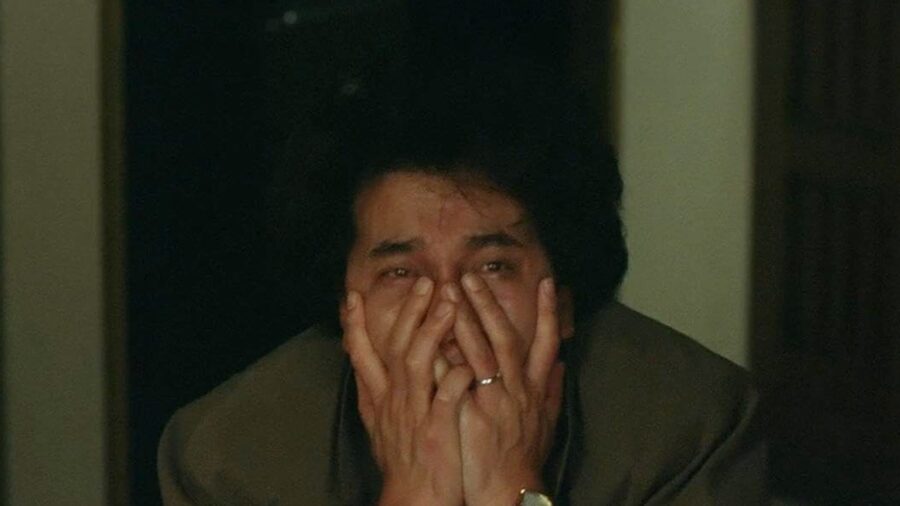

Plot-wise, the film centers around a detective investigating a series of brutal, gruesome murders. Each bears the same eerie signature: a gigantic X carved into the neck of the victims. But what distinguishes these killing is more than their abject brutality–indeed, it is the unsettling calm of the perpetrators—yes, perpetrators, plural—who have no recollection of their actions.

All of which suggests a horrifying level of psychological manipulation. That is, hypnosis.

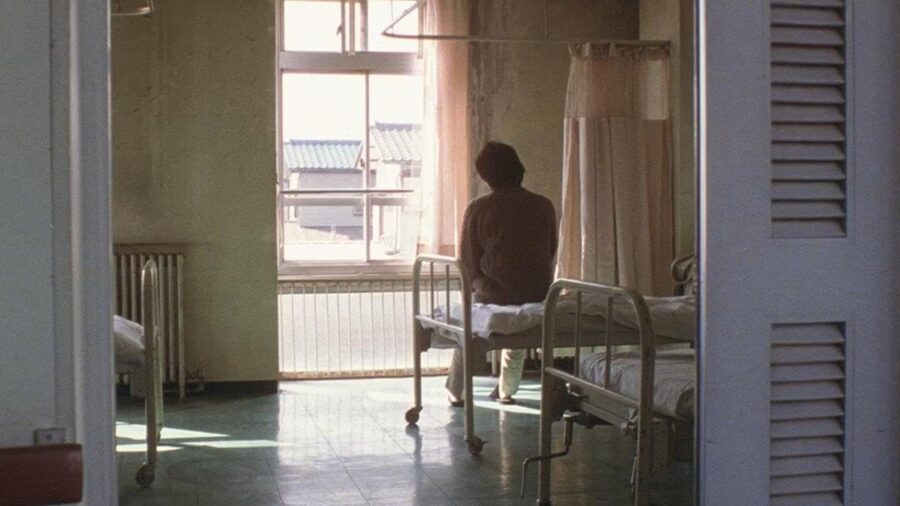

Thus, what could have been a campy, middling horror film born of this premise, instead amounts to anything but. Masterfully, Kurosawa’s direction in Cure employs long, static shots, forcing the viewer to inhabit the film’s world—a world that feels deeply familiar and profoundly alienating, like the static-ridden TV sets in The Ring.

A Simmering Horror

This is a world where horror never leaps from the shadows; instead, it seeps and fattens—a slow-burning terror forcing you to question the very nature of free will and the sad fragility of the human mind.

You Can Hear The Horror

The film is also a masterclass in sound design. The most ordinary of sounds—the clicking of a lighter as it produces a flame, a wheelchair rolling down a hallway, the humming of a clothes dryer—are craftily manipulated to a surprisingly evocative extent (which, in and of itself, harkens to hypnosis, one of the focal points of the film). Just as compellingly, and especially during sequences involving hypnosis, the sound in Cure will cut out entirely, engendering an atmosphere of dread even stronger than that wraught by the girl crawling out the TV in The Ring.

The cumulative effect of this special attention to sound is frankly devastating.

A Film Of Massive Influence

It’s hard to overstate the film’s influence on Japanese horror and global cinema as a whole. Predating Ringu, the movie is often considered the real catalyst for international J-Horror, which exploded soon after. Yet the sheer psychological depth and existential dread the film entails laid the foundation for the thematic and stylistic decisions defining global cinema, too, in addition to Japanese horror, as compelling as that nation’s horror exports are. Kurosawa made every inch of the mundane reality permeate with fear in Cure; this achievement challenged other filmmakers to rise to the creative occasion, particuarly Hideo Nakata with The Ring, and audiences benefited worldwide.

Moreover, Aster’s praise for the movie emphasizes it transcendent qualities. The film is simply and abundantly an excellent, almost excessively engaging experience. It contends with the human condition as energetically as great, non-genre films, or works from any other medium. Plus, its influence is readily observable in Aster’s films: the building of tension not through jump scares but through an immersive atmosphere of dread—alongside a narrative that digs deep into the darkest corners of the human psyche.