The Max Dark Dystopian Sci-Fi Classic Continues To Hypnotize Viewers Almost 50 Years Later

The 1979 Soviet film Stalker is widely regarded as a masterpiece of cinema. Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky from a script by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, it has had a profound influence on filmmakers and artists around the world. Based on the 1972 novel Roadside Picnic, the film is celebrated for its unique blend of science fiction, philosophy, and visual poetry.

Not The Kind Of Stalker We’re Used to

In the context of the film, the term “stalker” refers to individuals who illegally searched for and smuggled alien artifacts out of an area known as the Zone. Other options like “prospectors” and “trappers” were initially considered before settling on the phrase. The Roadside Picnic authors adapted the English word into Russian as “Stullker,” which gained popularity after being introduced by them.

The Story

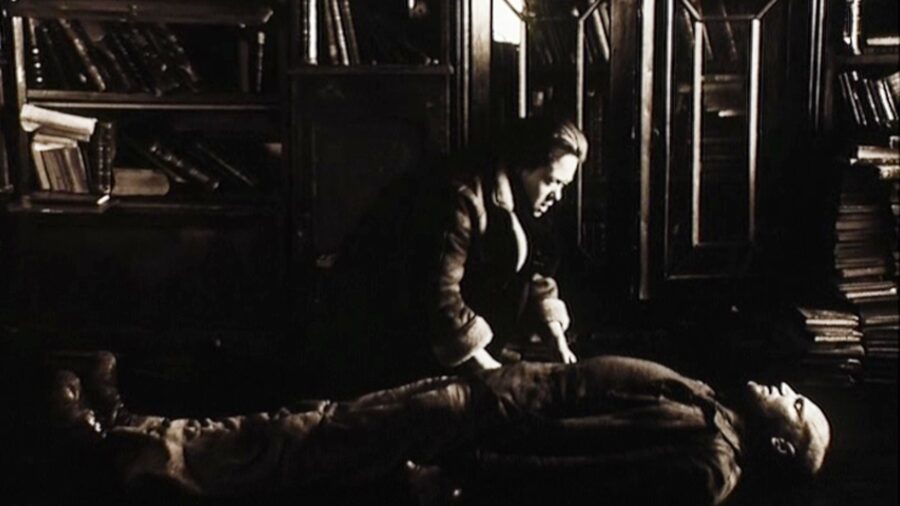

The story begins with a man who works as a Stalker (Alexander Kaidanovsky), guiding people through the Zone where the laws of physics bend and remnants of otherworldly activity linger among its ruins. Within the Zone lies a fabled place called the Room, rumored to fulfill the deepest desires of those who enter. The Zone is heavily guarded by the government and surrounded by supernatural dangers.

Despite his wife’s pleas, the Stalker sets out to guide his next clients – a Writer (Anatoly Solonitsyn) and a Professor (Nikolai Grinko) – into the Zone. Together, they navigate past military barriers and venture deeper into the Zone on a railway car. The Stalker warns his companions of the dangers and tests for hidden traps. Along the way, they discuss their motivations for seeking the Room.

The Writer seeks inspiration and is disillusioned with life, while the Professor is more rational and skeptical, seeking knowledge. The Stalker simply wants to help people reach their destination. Each character represents different facets of human nature and philosophy. Upon reaching the Room, tensions rise as they confront various moral dilemmas.

A Difficult Production

Stalker went through a tricky production as Tarkovsky spent a year shooting all the outdoor scenes. However, upon returning to Moscow, the crew discovered that the film had been improperly developed, resulting in unusable footage. The problem was due to a new type of Kodak film stock, 5247, with which Soviet labs were unfamiliar.

Moreover, relations between Tarkovsky and the original cinematographer, Georgy Rerberg, had soured. Upon seeing the poorly developed material, Tarkovsky decided to fire Rerberg and considered abandoning the project altogether. Eventually, Tarkovsky re-shot Stalker with new cinematographer Alexander Knyazhinsky.

Critics Initially Didn’t Know What To Make Of It

Stalker was met with a mixed reception upon its release due to its complex, ambiguous narrative and slow pacing. Some viewers found it to be a challenging and intellectually stimulating film, praising its philosophical depth and visual poetry. Others, however, found it tedious and difficult to follow. Still, the movie sold over four million tickets in the Soviet Union against a budget of 1 million roubles.

In Later Years, Appreciation For Stalker Grew

Over the years, Stalker has developed a cult following, admired for its atmospheric cinematography, haunting soundtrack, and thought-provoking storyline. Many appreciate its exploration of existential themes and the nature of reality. Critics have also offered more positive reevaluations of Stalker, recognizing its significance as a landmark of Russian cinema and a testament to director Tarkovsky.