3D-Printed Cages Allow For Better Bacteria Growth Than Petri Dishes

This article is more than 2 years old

Well, not quite, but putting two kinds of bacteria in a cage is one of the perks of a new use for 3D printing. There seems to be nothing 3D printers can’t do, including replacing petri dishes as the best venue for growing bacteria and reproducing environments in which microbes grow.

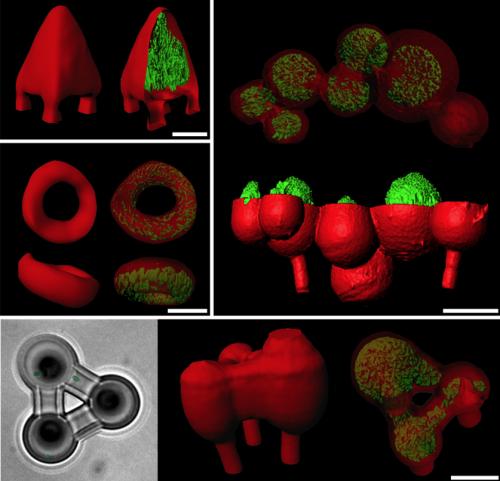

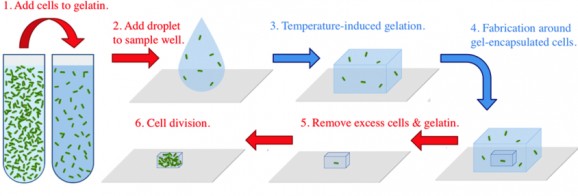

University of Texas scientists published a study detailing their use of 3D printing to build tiny habitats, or cages, to study bacteria. They start by putting bacteria in a gelatinous solution, which feeds them and promotes reproduction. The bacteria become fixed when the solution cools, at which point the scientists can figure out which bacteria they want to study and what shape they want the cage to be. They then project a 2D cage onto the gelatinous liquid and use that design for the 3D layering. High-precision lasers and hair-thin layers of protein form the 3D structure that completely contains the bacteria when it’s finished. After that, the scientists can decide which bacteria exist in each cage, as well as how much of those bacteria. This allows them to construct environments similar to those in humans and to observe signals from one community of microbes to another.

While petri dishes are all well and good, they don’t provide scientists with the same degree of insight when it comes to the roles shape, size, and density play in bacteria’s ability to cause disease. They’re focusing specifically on a staph bacteria that causes skin infections, and that develops antibiotic resistance when it interacts with another type of bacteria in cystic fibrosis patients. Scientists say that the cages allow the bacteria to “converse” with each other, allowing them to gain insights into how and why the antibiotic resistance forms when the two kinds of bacteria mix. When different types of bacteria enter the same environment, one generally exerts influence over the other — a cage match of sorts. Unfortunately, what often happens is that the bacteria that “wins” ends up acting like a super-charged version of one or both of the initial strains.

Most infections — at least, the really fun ones — aren’t limited to a single type of bacteria. Bacteria interact with each other and confer properties, such as antibiotic resistance, onto each other. These interactions will be easier to observe in the carefully regulated and monitored 3-D printed cages. And when you’ve got a bunch of cages, you’ve essentially got a zoo of bacterial communities, which isn’t exactly the panda cam, but is pretty exciting if you’re a scientist. The bacterial interactions could lend important insights into treatments, as well as initiate new types of experiments in which scientists are better able to replicate entire microbial environments.

This is also additional proof that pissing off scientists is a bad idea, unless you want to find yourself in a cage full of nasties.