Scientists May Have Found A New Type of Solid

This article is more than 2 years old

Scientists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in Maryland have found evidence for a substance that may represent a new category of solids. In a paper published by the Physics Review Letters, scientists describe the research they conducted at NIST and Argonne National Lab on a substance they’re calling “Q-glass.”

Q-glass is a metallic glass that seems to be neither crystal, glass, nor quasicrystal. “Everything you can think about this thing behaves like a crystal, except it isn’t,” says Dr. Lyle Levine, a researcher on the project.

Solid crystals have an ordered, rigidly patterned atomic arrangement, which gives crystals something called “translational symmetry,” which means that any section of a crystal will fit into a new position after being slid up, down, in, out, or sideways. Crystals also contain rotational symmetry, which means that the object can be rotated and it still looks the same and maintains the same atomic alignment.

Glass is pretty much the opposite — its atoms aren’t symmetrical, and they are randomly arranged. The common way of describing the atomic arrangement of glass is that it looks like someone flash-froze a liquid before its atoms had a chance to order themselves.

Then there’s quasicrystals, a new category of solids discovered in the 1980s by a NIST guest researcher who received the Nobel Prize for his work (see the video below). Quasicrystals behave mostly like crystals, but a little bit like glass — they have a fixed atomic composition, as well as rotational symmetry, but they don’t have translational symmetry or a long-range atomic pattern.

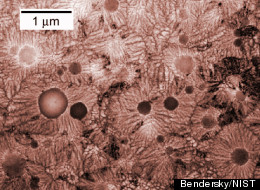

Q-glass is a different story altogether. Like glass, it has neither rotational nor translational symmetry, but unlike glass, its atomic arrangement doesn’t appear to be random. It appears to grow from “seeds” or “nodules,” and as it does, “every atom still knows where to go.” It’s unclear what determines the arrangement of the atoms, but something does. When scientists heated up Q-glass and then cooled it in a silicon, iron, and aluminum mixture, they observed that it excluded atoms that didn’t fit. “It’s rejecting atoms that aren’t fitting into the structure, and if there’s no structure, it’s not going to be doing that,” says Levine. He went on to call it the “strangest material I ever saw.”

Scientists conducted a bunch of experiments at Argonne’s Advanced Photon Source, going through a list of possible explanations for the strange behavior of Q-glass. One by one, they were able to disprove or eliminate possible theories, leaving two possibilities: the first is that the substance is essentially trying to behave like a crystal or quasicrystal, but something interrupted that process on a structural level, or that Q-glass is an entirely new atomic structure. I’ll go ahead and vote for the latter, just in case anyone’s wondering. All I know is, that Q-glass is solid!