Extinct Animal Brain Scan Reviving Fearsome Predator?

Science has changed in big ways over the last 140 years and finally, over a century of research is paying off as the study of a thylacine brain has finally made its way into the scientific journal, PNAS. Better known as the Tasmanian tiger, the thylacine is considered to closely resemble wolves but is closer in size and shape to dingos and falls into the category of carnivorous marsupials versus canids. With the recent step forward in understanding the extinct animal’s genetic brain makeup, researchers are that much closer to perhaps finding a way to bring the creature back from the beyond.

Thylacines officially went extinct almost a century ago on September 7, 1936, when the last creature of its kind died at Hobart’s Beaumaris Zoo in Australia. The dingo-like animal’s death wouldn’t be completely in vain as the day went down in Australia as the National Threatened Species Day – a commemorative date to spread awareness on how humans affect the world around them.

Prior to dwindling in size, the marsupials were one of many critters living in Australia and New Guinea before humans took over the land, pushing them to inhabit Tasmania somewhere around 3,000 years ago.

Brain scans of the extinct thylacine, aka Tasmanian tiger, could reveal the secrets of reviving the carnivore.

The thylacine brain reported in the recently published study wasn’t the animal that perished at Hobart’s Beaumaris Zoo but instead, one that had died in the Berlin Zoo all the way back in 1880. Managing to preserve the organ for well over a century, the brain sample is a scientific feat as it was able to survive not one but two world wars and the rebuilding of the country following the heavy bombing.

Furthermore, the results of the research are fascinating when it’s taken into account just how little information about the thylacine was there for researchers to sink their eyes into as its sex and body weight were just two of the important factors missing from the information.

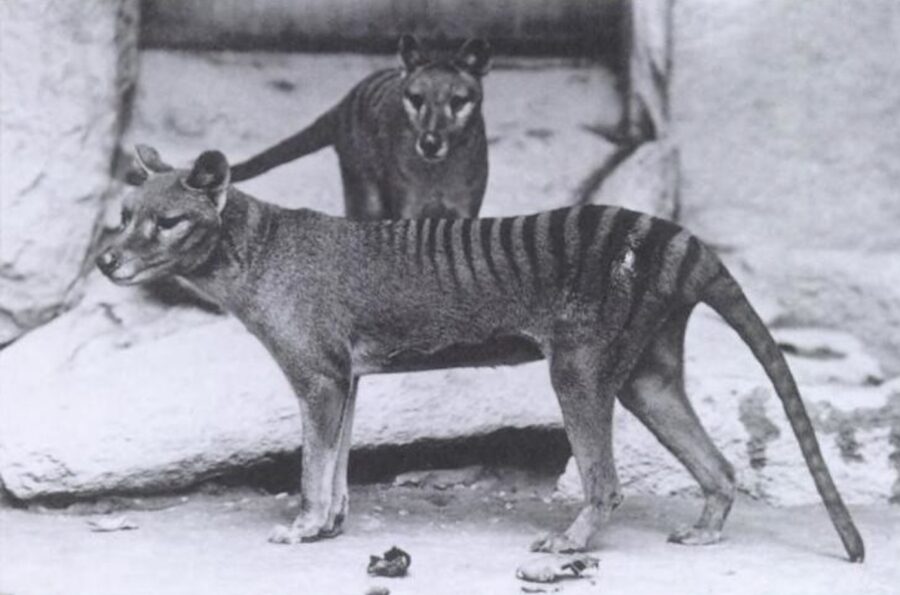

Although the thylacine may look like our four-legged best friends, the animal that once ran wild in Australia and Tasmania was anything but, closer related to Tasmanian devils and dunnarts.

At first glance thylacine closely resembles a wolf or a dog, or another member of the Canidae family. With a wolf-like face that features a long snout and pointed ears, the creature’s face could easily be mistaken for one of these examples while its striped body and long tail give it a tiger-like twist.

Thylacines officially went extinct almost a century ago on September 7, 1936, when the last creature of its kind died at Hobart’s Beaumaris Zoo in Australia.

The phenomenon of the thylacine instead being a carnivorous marsupial is considered to be part of a scientific process known as evolutionary convergence which happens when the body shapes of animals from different lineages make them appear to be from the same background.

Although the thylacine may look like our four-legged best friends, the animal that once ran wild in Australia and Tasmania was anything but, closer related to Tasmanian devils and dunnarts. In the study of the critter’s brain, it was discovered that the cerebral cortex was larger than in other animals of the same background, which points to the likely fact that this species was one that highly relied on its sense of smell for scavenging and hunting.

With scientists making impressive moves forward in studying the human brain, the latest published research on the thylacine helps bring a long-extinct species back to life for us to better understand the lost animals from decades ago and could possibly even lend a hand to those focused on the evolution of life.