Scientists Are Using Ravenous Bacteria To Save The Planet

A group of Japanese scientists made an important discovery while investigating a trash dump in 2001. In an article published by The Guardian, the scientists, led by Kohei Oda, found a slimy film of bacteria that had been successfully feeding on (and thus breaking down) various plastics in among the waste.

A chance discovery led to a ground-breaking study into the usage of plastic-eating bacteria.

The bacteria were not only breaking down the plastics, but they were using the harmful carbon produced from the material as fuel to energize their own growth and replication. The discovery of a plastic-hungry bacteria was groundbreaking; however, there were still plenty of unanswered questions to explore.

The road from discovery to everyday integration into the role of plastic recycling wasn’t going to be simple. Discovering a bacteria capable of feeding on the breakdown of plastic wastes was just the beginning.

In the 20+ years since Oda and his team discovered the bacteria, only some movement has been made toward integration. Any vast forward progression would have to be fueled by a growing interest in the project, and the interest hasn’t been there thus far.

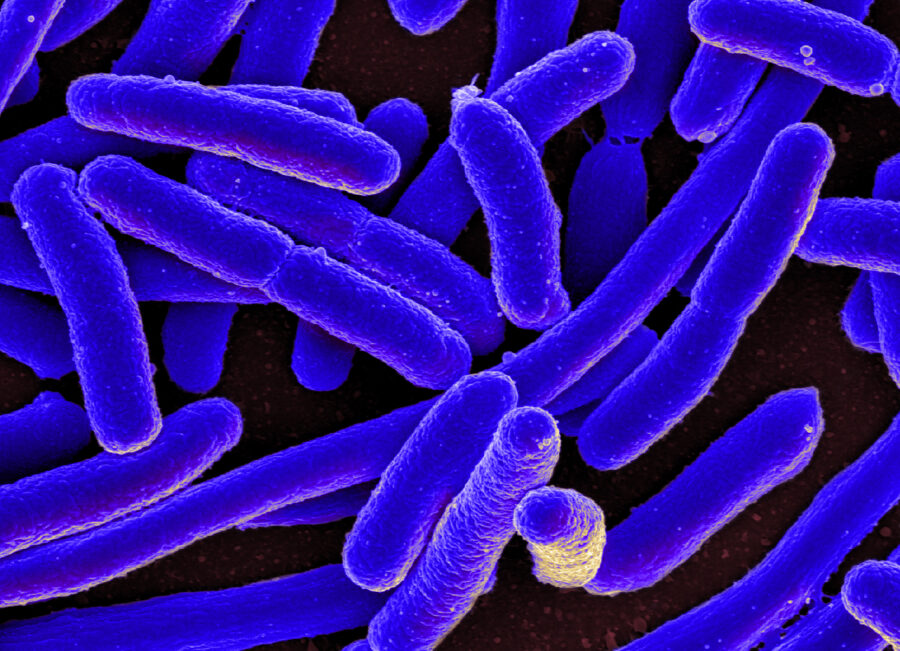

The study of microbes and other bacteria has been largely stifled in recent times due to the scientific community’s questioning of their true potential. Kohei Oda believes that this part of nature “often has very good ideas” for solving the scientific mysteries faced by our world.

If we have yet to figure out a good solution, microbes and bacteria have likely already sorted the situation. The challenge is to find which bacteria is most efficiently suited for the job. The bacteria Oda and his team discovered was useful, but not efficient.

Discovering a bacteria capable of feeding on the breakdown of plastic wastes was just the beginning.

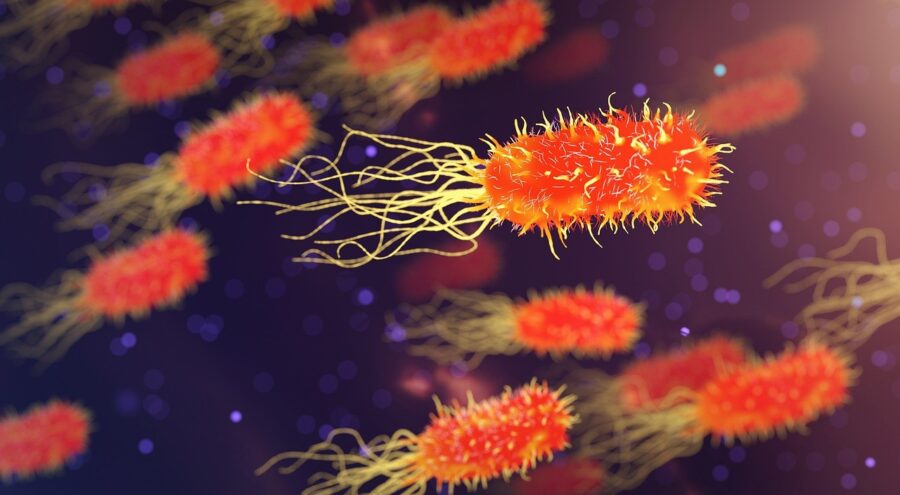

In a lab test, Oda’s bacteria (which he named Ideonella sakaiensis) was able to break down a 2cm-long piece of plastic weighing only one 20th of a gram in around seven weeks. Watching the newfound bacteria at work is noteworthy, but the pace it set on the breakdown of the plastic would need boosting.

The world’s plastic problem is far too widespread to wait seven weeks for only a 2cm piece of plastic to be recycled. With an island of plastic floating in the Pacific Ocean and only around nine percent of all the world’s plastics ever truly being recycled, the problem is overwhelming.

France is the only country so far that has made any notable forward progress in the situation. A company by the name of Carbios has successfully integrated the use of bacterial enzymes to process and recycle 250kg of PET (polyethylene terephthalate) plastics daily. They break the plastic down into its precursor molecules, and the result of that process can be used to create new plastics.

This is important because, before now, plastics haven’t truly been fully recyclable. The typical process of plastic recycling breaks down the material, making it a little thinner and weaker after every remolding process, eventually ending up as unusable waste.

For the bulk of the last 200 years, scientists have limited the use of bacteria microbes, as they have widely been seen as something to be eradicated. Industrially, they have only been put to work in processes such as the fermentation of wine or cheese, but Carbios has found a way to put Oda’s plastic-hungry bacteria to work in a more ecologically beneficial manner.

Carbios developed a process that breaks down the trashed plastics into small pellets, which are composed of a much less compact group of fibers, giving the bacteria a bigger area to attack.

For the bulk of the last 200 years, scientists have limited the use of bacteria microbes, as they have widely been seen as something to be eradicated.

Naturally, the bacteria used to break down the plastics would produce other enzymes and waste products, but Carbios pays a biotech company to produce large, concentrated collections of the plastic-eating enzyme from bacteria. When the plastic pellets are placed in a large churning metal bin, the enzyme breaks the plastic down into a liquid made up of two chemicals that can then be used to create new plastics.

In the future, one could be hopeful that France’s methods will spread and be refined by other countries, spawning a vast progression in the world’s battle against overwhelming plastic waste.