Experimental Ebola Serum Appears To Be Working On U.S. Patients

This article is more than 2 years old

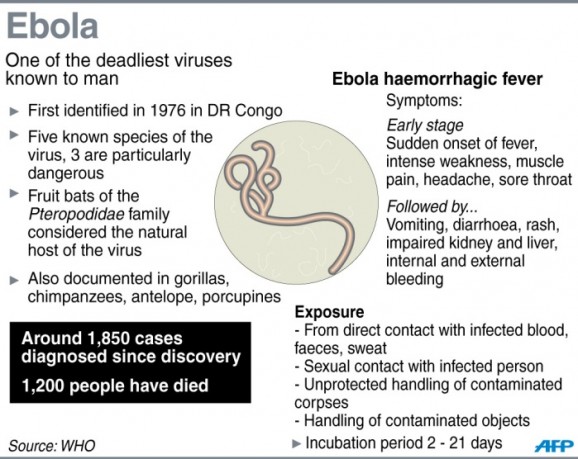

So, this Ebola thing…holy effin’ shit about sums it up, I think. Every time I read another article about it, the disease seems worse and worse. Just this morning I saw a headline claiming that the outbreak could be “much worse than thought.” It’s hard to wrap your mind around that idea. According to the World Health Organization, the virus has caused 887 deaths, but some medical personnel in West Africa say that there are many more cases going unreported. Without medical treatment, this strain of Ebola has a 90% mortality rate. Part of the reason the outbreak is so bad is that unlike previous ones, one of the epicenters this time is a major city, Monrovia, the capital of Liberia, home to roughly a million people. There are many reasons to be concerned about this outbreak. According to the CDC has already also wreaked havoc in Guinea and Sierra Leone and is now spreading into Nigeria. There are, however, reasons to be cautiously optimistic, namely that an experimental serum seems to be helping two Americans infected with the disease.

So, this Ebola thing…holy effin’ shit about sums it up, I think. Every time I read another article about it, the disease seems worse and worse. Just this morning I saw a headline claiming that the outbreak could be “much worse than thought.” It’s hard to wrap your mind around that idea. According to the World Health Organization, the virus has caused 887 deaths, but some medical personnel in West Africa say that there are many more cases going unreported. Without medical treatment, this strain of Ebola has a 90% mortality rate. Part of the reason the outbreak is so bad is that unlike previous ones, one of the epicenters this time is a major city, Monrovia, the capital of Liberia, home to roughly a million people. There are many reasons to be concerned about this outbreak. According to the CDC has already also wreaked havoc in Guinea and Sierra Leone and is now spreading into Nigeria. There are, however, reasons to be cautiously optimistic, namely that an experimental serum seems to be helping two Americans infected with the disease.

You might have seen the video of Dr. Kent Brantly walking from an ambulance into Emory University Hospital last week (sadly, a patient used a cell phone to record the transfer when a nurse told her what was going on—so much for privacy and respect, I guess). Brantly had been working in at a hospital in Liberia as part of the aid organization Samaritan’s Purse when he contracted the virus. At the first hint of symptoms he quarantined himself and a test confirmed that he had the disease. Over the next nine days, his condition deteriorated to the point that he called his wife to say goodbye. That’s when he received an experimental drug called ZMapp, developed by a San Diego-based biotech firm.

Mapp Biopharmaceutical, Inc is part of a consortium that got a big grant from the NIH, as well as funding from DARPA and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) to create the new drug. Produced by exposing mice to ebola and then harvesting their antibodies, a published study revealed positive effects of the drug on primates. 100% of them survived when given the drug 24 hours after exposure to the virus; half survived when treated 48 hours after exposure. After that, survival rates drastically decline; five days seemed to be about as long as an infected monkey could hold out. Brantly received the serum nine days after diagnosis, along with another doctor, Nancy Writebol, who had been sick for six days.

Mapp Biopharmaceutical, Inc is part of a consortium that got a big grant from the NIH, as well as funding from DARPA and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) to create the new drug. Produced by exposing mice to ebola and then harvesting their antibodies, a published study revealed positive effects of the drug on primates. 100% of them survived when given the drug 24 hours after exposure to the virus; half survived when treated 48 hours after exposure. After that, survival rates drastically decline; five days seemed to be about as long as an infected monkey could hold out. Brantly received the serum nine days after diagnosis, along with another doctor, Nancy Writebol, who had been sick for six days.

The serum was frozen for shipment to Liberia, and as it thawed, Brantly’s condition grew dire. Doctors dosed him with the medication and within an hour, he started to improve. The next day he was able to get on a jet for the U.S. Writebol’s response wasn’t quite as dramatic, though after a second dose she, too, was in stable enough condition to be transported back to the U.S. Both doctors continue to show sustained improvement.

The serum isn’t ready for widespread use, unfortunately. It hasn’t undergone clinical trials, much less been approved by the FDA for human use. However, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has a “compassionate use” clause which allows for such use of experimental drugs. Hopefully the current situation will underscore the need to start those clinical trials soon and get this serum on the path toward widespread availability.

Leave a comment

You must log in to post a comment