Uncovered Archives Offer A Glimpse Into Octavia Butler Books That Could Have Been

This article is more than 2 years old

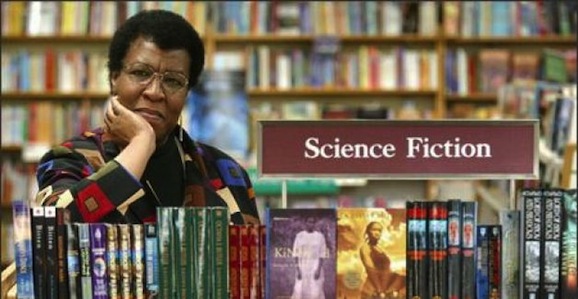

Octavia Butler was one of the greatest minds modern science fiction. A sudden stroke took her life eight years ago in her Seattle home before she was able to complete one of her most recent trilogies, the dystopian Parable novels. A notorious rewriter, scholars have been going through a collection of papers Butler left to the Huntington Library, and are getting a clearer picture of what her final book could have looked like.

Octavia Butler was one of the greatest minds modern science fiction. A sudden stroke took her life eight years ago in her Seattle home before she was able to complete one of her most recent trilogies, the dystopian Parable novels. A notorious rewriter, scholars have been going through a collection of papers Butler left to the Huntington Library, and are getting a clearer picture of what her final book could have looked like.

Upon her death, the Hugo and Nebula award-winning Butler left boxes and boxes of notes, drafts, revisions, journals, and more to Huntington. A literary scholar named Gerry Canavan, from Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, has started the process of sifting through this treasure trove, and has unearthed a wealth of new information. This provides a glimpse into her overall writing process, but also an idea of where her writing was headed in the future.

One of the things Canavan found was that Butler was prone to turning out multiple drafts, not an uncommon practice, but making significant changes to the overall architecture along the way. He also found evidence of numerous starts and stops for many of her novels, and much that was discarded or left out of the finished books. In fact, much of what he discovered that remained on the proverbial cutting room floor, tended to be much bleaker and less optimistic than the material that appears in the final product.

Writing in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Canavan goes into great depth about Butler’s attempts, more accurately struggles, to finish the Parable series. He writes:

Nearly all of the texts focus on a character named Imara — who has been named the Guardian of Lauren Olamina’s ashes, who is often said to be her distant relative, and who is plainly imagined as the St. Paul to Olamina’s Christ (her story sometimes begins as a journalist who has gone undercover with the Earthseed “cult” to expose Olamina as a fraud, and winds up getting roped in). Imara awakens from cryonic suspension on an alien world where she and most of her fellow Earthseed colonists are saddened to discover they wish they’d never left Earth in the first place. The world — called “Bow” — is gray and dank, and utterly miserable; it takes its name from the only splash of color the planet has to offer, its rare, naturally occurring rainbows. They have no way to return to Earth, or to even to contact it; all they have is what little they’ve brought with them, which for most (but not all) of them is a strong belief in the wisdom of the teachings of Earthseed. Some are terrified; many are bored; nearly all are deeply unhappy. Her personal notes frame this in biological terms. From her notes to herself: “Think of our homesickness as a phantom-limb pain — a somehow neurologically incomplete amputation. Think of problems with the new world as graft-versus-host disease — a mutual attempt at rejection.”

From here the possible plots begin to multiply beyond all reason. In some of the texts, the colonists are in total denial about the fact that they are all slowly going blind; in others the blindness is sudden, striking randomly and irreversibly; in others they all begin to go insane, or suffer seizures, or mad rages, or fall into long comas; in still others they begin to hurt and kill each other for no other reason than the basic inevitable frailty of human nature (the same, alas, on any world). In one of the versions of the novel the colonists develop a telepathic capacity that soon turns nightmarish when they are unable to resist it or shut it off; in one twist on this idea it’s only the women who are so empowered, with the men organizing a secret conspiracy to figure out how they might regain control.

There’s a version where the blindness and the telepathy are linked; Imara becomes able to see out of others’ eyes as she loses the ability to see out of her own. In some Imara finds she needs to solve a murder, the first murder on the new world; in still others Imara herself is murdered, but discovers that on this strange alien world she is somehow able to haunt another colonists’ body as a ghost, replicating Doro’s power from the Patternist books and thereby linking even the Parables to the speculative universe she first developed as a teenager. Sometimes Imara is an Earthseed skeptic; other times she is a true believer; sometimes she is, like Olamina, a hyperempath; still other times the cure for “sharing” has been discovered in the form of an easy, noninvasive pill. Sometimes Bow is inhabited by small animals, other times by dinosaur-like giant sauropods, and still other times by just moss and lichens; sometimes the colonists seem to encounter intelligent aliens who might be real, but might just be tokens of their escalating collective madness; and on and on and on.

One version of the blindness narrative is abandoned with no small grumbling after José Saramago wins the Nobel Prize for Blindness in 1998; another is put aside after she determines it’s just too similar to Kim Stanley Robinson’s famous Red Mars; still another is abandoned shortly after Butler frustratedly, self-loathingly declares Imara to have “a personality more like mine” against Olamina’s “super me — the me I wish I was.” Sometimes Earthseed seems more like a self-help philosophy; sometimes it becomes a genuinely mystical, transcendent religion; sometimes we see it begin to shift from the first toward the second; sometimes it suffers schisms, heresies, and purges. Sometimes Imara is a former cop; sometimes she is a trained psychologist; sometimes she’s a doctor; sometimes she’s that undercover journalist; still other times she was the victim of a horrific series of rapes as a child, saved by one of Olamina’s orphanages when no other entity or institution would bother. When Butler begins writing the book, Newt Gingrich is named as the model for the central antagonist; in the versions from the 2000s, it’s George W. Bush; sometimes in between it’s other science fiction writers with whom Butler didn’t especially get along.

Parable isn’t the only series left incomplete at the time of Butler’s 2004 death. Her last published novel, Fledgling, was a new interpretation of the vampire myth, and the start of something much larger. Io9 contacted Canavan to see if she left any hints or ideas about where that story was headed. While there isn’t much more than ideas and a few loose outlines, it does sound like she had plans for this arc in the future. Some of her notes included plans for novels featuring recurring characters and protagonists, while there are even some that detailed a vision for novels set generations in the future.