Scientific Study Of Herpes Confirms Human Migration Patterns

This article is more than 2 years old

Scientists who want to examine human evolution can study skulls or, as a new study confirms, they can track something that humans have had to deal with for thousands of years: herpes.

Scientists who want to examine human evolution can study skulls or, as a new study confirms, they can track something that humans have had to deal with for thousands of years: herpes.

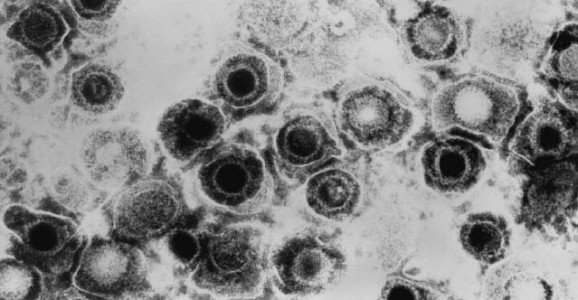

Turns out herpes, specifically the herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) strain, which is associated with cold sores, has been around for a long, long time. It’s generally not particularly harmful (HSV-2, not HSV-1, is responsible for most genital herpes, FYI), but it’s robust and highly infectious. It’s been part of the human condition for so long that researcher Curtis Brandt of the University of Wisconsin-Madison refers to it as “a kind of external genome.”

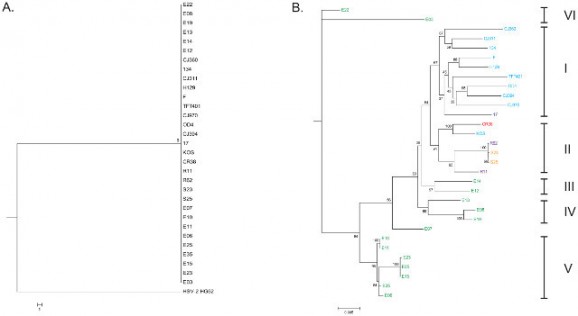

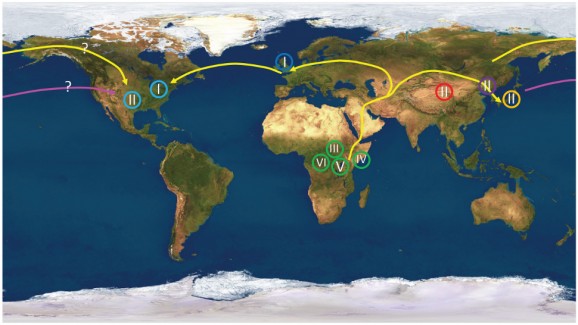

Brandt and his colleague Aaron Kolb studied 31 HSV-1 strains from North America, Europe, Asia, and Africa. They then mapped the mutation of the virus, which allowed them to chart the way humans took the disease with them as they spread out across the Earth. The researchers used genetic sequencing and bioinformatics to sort out the data contained in those 31 strains, focusing mainly on the changes in the base sequences of the genome. They were able to create a herpes family tree that tracked common ancestors between the various strains, eventually linking the family tree into a complete genomic network.

As the different strains became associated with locations, Brandt and Kolb were able not only to map the virus’s spread, but also the spread of humans. I’m sure anthropologists appreciate the fact that their findings support previously held beliefs that humans come from Africa and then migrated to Europe and Asia, and then crossed the then-existing land bridge to North America. Their research confirmed clusters that correspond to locations — there’s a group of African isolates, clusters between strains from the Far East, etc. The African strains were the most diverse, further supporting the theory that humans originated in Africa.

The American samples of HSV-1 all matched the European strains, which also makes sense. There was one anomaly — an isolated strain from Texas. Brandt and Kolb have two possible theories for this exception, that the sample came from a Far East immigrant or that it came from a Native American whose distant relatives were among those to cross via the land bridge many millennia ago.

Who knew herpes could actually be useful, or dare I say, even kind of neat? We may not need cold sores to discern our origins, but I have to admit, science has some unique ways of fact-checking itself. And as technology continues to develop at such a rate that we’re increasingly forced to contemplate what makes us human, we have a solid scientific answer to fall back on. It may not be glamorous, but we could have worse legacies.