3D-Printed Cast Speeds Healing And 3D-Printed Cartilage Fights Arthritis

This article is more than 2 years old

It’s been at least a few days since we’ve extolled the virtues of 3D printing here on GFR, so we’ve got some catching up to do! Remember back in the day when breaking a bone meant getting a huge cast that made you sweat and itch so you’d have to scratch in there with a coat hanger? Aside from getting people’s autographs, those casts pretty much sucked. Thanks to 3D printing, casts have gotten way cooler looking, as well as more effective.

It’s been at least a few days since we’ve extolled the virtues of 3D printing here on GFR, so we’ve got some catching up to do! Remember back in the day when breaking a bone meant getting a huge cast that made you sweat and itch so you’d have to scratch in there with a coat hanger? Aside from getting people’s autographs, those casts pretty much sucked. Thanks to 3D printing, casts have gotten way cooler looking, as well as more effective.

A new 3D-printed cast designed by Deniz Karasahin not only keeps bones stable in a cast far lighter and more aesthetically pleasing than white plaster, but also speeds up healing when hooked up to a Low-Intensity Ultrasound (LIPUS). LIPUS sends high frequency sound wave pulses, which induce cartilage and bone cells to incorporate more calcium ions.

A few years ago a study indicated that LIPUS “significantly reduce[d] healing time” in three of the seven patients in the trial. Another study indicated that the use of LIPUS sped up healing by 24-42% when used on newly broken bones, and particularly when used by patients who had factors that would have otherwise complicated their healing.

Typically, someone undergoing LIPUS would trek to a medical clinic on a daily basis, but incorporating a portable ultrasound system into a cast removes that inconvenience. Karasahin says that only 20 minutes a day can generate the kind of best-case results found in the studies. The challenge in incorporating the ultrasound generator is that it needs to touch the skin — something that would have been impossible with a conventional cast. So Karasahin uses a 3D-printed exoskeleton cast called the Cortex, which is what you’d get if you tried to design a cast that resembled fishnet stockings. The cast is made in two halves that snap together, and the holes are fewer and smaller near the site of the fracture, though still big enough to attach the LIPUS system. Pretty soon these will come in an array of colors, and if you break both arms, you could sport a Wonder Woman look.

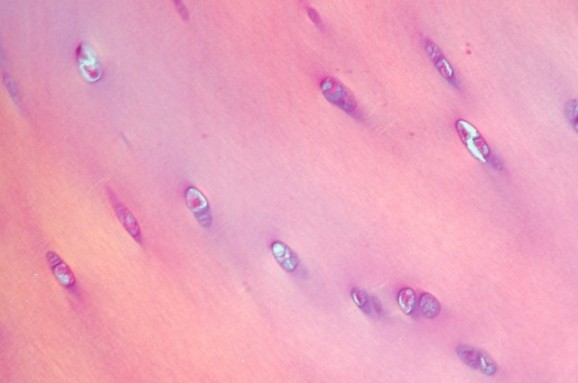

Couple that with a recent advance in the 3D printing of cartilage and you’ve got a good week for medical science. A University of Pittsburgh researcher recently presented a method for “made to order” cartilage to combat osteoarthritis, a disease that currently has no cure. Osteoarthritis involves the drying up of cartilage over time, resulting in severe pain that only joint replacement can permanently alleviate.

Using a patient’s own stem cells, in a process not unlike the one that allowed doctors to implant lab-grown vaginas in four women, researchers can create cartilage that can be added to the depleted cartilage in a patient’s joint. Eventually, researchers hope to be able to print the cartilage right into the joint with a printer or nozzle shaped like a catheter.

The list of body parts that haven’t been 3D-printed continues to shrink. Even so, I’m betting we’ll cover a story in the near future that crosses at least one more of those off the list.