Scientists Attempt To Clone Extinct Frog With Unique Reproductive Traits

This article is more than 2 years old

If you’re familiar with the southern gastric brooding frog (Rheobatrachus silus), the Queensland, Australia-found species that has been extinct for around 30 years, then you’re either seriously into frogs — and no one here is going to judge you for it — or perhaps you’ve read about its bizarre method of childbirth by way of regurgitation. It’s hardly the only frog to have stopped hopping the earth, but steps are being taken to clone it right back into the ecosystem. And off in some past divergent track of space-time, a teenage Michael Crichton takes note.

Frogs have seen a steady decline in population for myriad reasons, including heavy foresting, environmental changes, and the proliferation of the chytrid fungus, which clogs the animals’ pores and dehydrates them. Mike Archer of the University of New South Wales has been trying to grow a gastric brooding frog’s embryo inside the body of its reasonably close relative, the barred frog. It isn’t exactly like putting a frog embryo jigsaw puzzle together. (Worst Christmas gift ever, by the way.)

We only know about the gastric brooding frog, discovered in 1972, thanks to the tireless work of ecology researcher Mike Tyler, who brought news to the world of its strange reproductive system, which consisted of halting production of the stomach’s hydrochloric acid in order to swallow the eggs, with mucus from the growing tadpoles’ skin further keeping the acid from producing. Once the eggs were in place, the mother could no longer eat, and when the tadpoles grew to the point that her lungs collapsed, she had to breathe through the skin. Eventually the frog gave birth by spewing froglet-filled vomit all over the place, and a new generation is born. Tyler published his description of the process in 1981, but the species faced a rapid extinction from 1979-1981, and the last captive member died in 1983. Though a northern gastric brooding frog species was discovered in 1984, it faced extinction just one year later.

Archer’s work is only possible due to tissue samples Tyler still had in freezers. Though the samples were damaged, they were still intact and useful. The next setback involved the barred frog’s egg-laying only taking place once a year, which hindered the experiments. But once it began, Archer and his team destroyed the nuclei from hundreds of the barred frog’s eggs and replaced them with those of the frozen tissue.

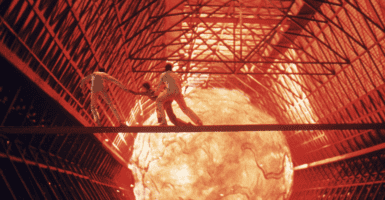

Finally, it worked! One egg split into two, and two into four, and so on. However, in this and in other successful attempts, the ball of cells begin to turn inward on itself through gastrulation, and then everything stops. That’s as far as they’ve gotten. But instead of discouragement, the team is ever optimistic. Similar experiments using the eggs of living species have ended in the same way, which suggests either equipment or procedure problems, rather than the science not working out.

Though Archer has seen detractors on almost all fronts, he doesn’t see his work as ethically or scientifically misguided. “No matter how many resources we put into looking after the environment, wildlife is no longer safe in the wild,” he says. “If we accept that maintaining biodiversity is important, we can’t assume that if you whack a fence up, everything’s going to be okay. You need to explore lots of parallel strategies.”

How do you guys feel about it? I mean, beyond having awesome YouTube videos of frogs vomiting babies and all.