Why Reading More Books Should Be A New Year’s Resolution

This article is more than 2 years old

There have been many science stories recently about how various technologies, including light exposure, optogenetics, and even playing computer games can improve brain function. People who follow these studies might think that the technology is the best brain food, but a recent study shows that reading books can boost our brains for days.

There have been many science stories recently about how various technologies, including light exposure, optogenetics, and even playing computer games can improve brain function. People who follow these studies might think that the technology is the best brain food, but a recent study shows that reading books can boost our brains for days.

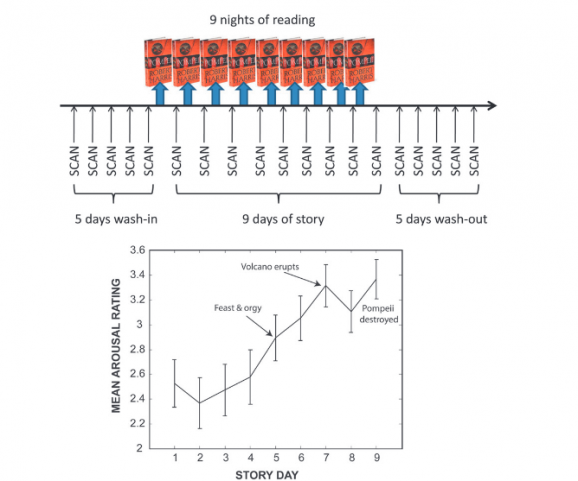

Scientists at Atlanta’s Emory University wanted to know what happens to the brain when we read. Obviously some stories really get into our heads and change us, but they wondered if that translated into anything neurologically measurable. The scientists found 21 subjects, all undergraduate students. They took fMRI scans of their brains while they rested as a baseline. Then, over the course of nine nights, the subjects read 30-page sections of Pompeii by Robert Harris. I haven’t read the book, but apparently it’s a page-turner, which merges fictional and non-fictional events surrounding the volcano outside of Pompeii. The subjects were sometimes asked to read it casually, and other times asked to read it deeply, like one would for a class.

Each morning, the team scanned their brains again, and continued the scans for five days after the subjects completed the book. The results, published their study in this month’s Brain Connectivity, indicated heightened brain connectivity in every morning brain scan, as well as in the scans for each of the five days after they finished the novel. Scientists identified greater connectivity in the subjects’ left temporal cortex, which makes sense given its association with language. They also found heightened connectivity in the central sulcus of the brain, which is located in the cerebral cortex and separates the cerebrum’s frontal and parietal lobes, which control motor skills and sensations.

Scientists were surprised to find enhanced connectivity in areas of the brain associated with movement and sensory information, and theories that “perhaps the act of reading puts the reader in the body of the protagonist.” The longevity of the effects was also surprising, and confirms that our brains respond to what we read for long after we read it — this is similar to building muscle memory and is something scientists call a “shadow activity.” This finding has particularly important implications for kids and the relationship between reading and brain development. The study also contributes to an emerging interdisciplinary field called literary neuroscience, which sounds like pretty much the most awesome field ever.

I always resolve to read more books in the coming year — this time, I’m even more adamant about it. Who’s with me? For those of you in need of reading suggestions, maybe the retrospectives on Arthur C. Clarke and Philip K. Dick will give you some ideas. Fortunately, the study didn’t indicate that reading classic or boring literature boosts the brain more than reading science fiction. In fact, I wouldn’t be surprised if it were the opposite, but that’s another study for another time.