Ray Bradbury’s Vintage 1939 ‘Zine Is Online For Your Eyeballs

This article is more than 2 years old

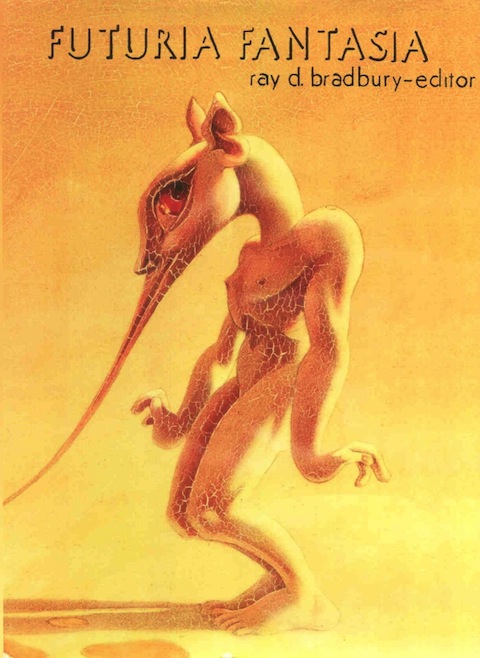

If I could meet anyone, past or present, it would be Ray Bradbury. The guy is my hero. I teach The Martian Chronicles every fall, and without exception, the students eat it up. As Bradbury passes into a somewhat godlike immortality, as both an author and personality, more and more Bradbury-related relics surface. All of them are interesting, but especially Futuria Fantasia (is that a Bradbury name or what?), the magazine Bradbury started in 1939 shortly after graduating from high school. Four issues of the magazine are now available online at Protect Gutenberg, and the first issue is even free.

If I could meet anyone, past or present, it would be Ray Bradbury. The guy is my hero. I teach The Martian Chronicles every fall, and without exception, the students eat it up. As Bradbury passes into a somewhat godlike immortality, as both an author and personality, more and more Bradbury-related relics surface. All of them are interesting, but especially Futuria Fantasia (is that a Bradbury name or what?), the magazine Bradbury started in 1939 shortly after graduating from high school. Four issues of the magazine are now available online at Protect Gutenberg, and the first issue is even free.

Bradbury started the magazine with a $90 loan from Forrest Ackerman—otherwise known as the “Ackermonster”—a writer, editor, literary agent, and collector of sci-fi memorabilia. Ackerman, who Bradbury met via the L.A. Science Fiction Society, had his own zine, Imagination!, and was the first to publish Bradbury, his 1938 story called “Hollerbochen’s Dilemma.”

Although Bradbury refers to the 1942 story “The Lake” as the one in which he finally found his voice as a writer, Futuria Fantasia is unmistakably his. In the first issue’s introductory note, Bradbury admits that publication had been planned for the previous year, but “when the door to the office was opened unexpectedly a white gusher of manuscripts and relatives spewed out. More than once Ye Editor was suffocated unto death by the musty volumes that poured in from all over Los Angeles. And then—someone turned off the financial faucet—leaving us all soaped up, but with no water!”

The issue includes a piece Ackerman wrote when he was 16, a poem by Bradbury, and a story by Ron Reynolds, a “new fan author,” who was actually none other than Bradbury himself. He encourages readers to send him mail if they enjoy the magazine, or “Appoint yourself as A-l mourner and critic and pound away at the mag.”

Listen to Bradbury and others read the contents of the Spring 1940 issue of Futuria Fantasia here.

The Reynolds story, “Don’t Get Technatal,” features dialogue that many would have recognized as Bradbury’s even if we didn’t know that he was behind the pseudonym. The story is about an aspiring writer who bemoans the fact that futuristic technology has cured the world of sadness and thus, made it impossible to write. But he quickly figures out a solution to that problem: “‘Jumping Jigwheels!’” he cried. ‘Why didn’t I think of it before! Robots! I’ll write a love story about two robots.’” Given what we know now of Bradbury’s work, that statement is wonderfully prophetic. Also indicative of Bradbury’s future work is a twist ending involving an atomic gun.

Bradbury, who wrote poetry throughout his entire life, included his poem “Thought and Space” in the issue. It begins and ends, “Space—thy boundaries are / Time and time alone.” Reading this early work, it’s clear he was still working out his voice and style, but his heart has always lived on the page. He’s one of those rare souls that was the same boy at 90 as he was at 18, and that, at 18, had a tender wisdom far beyond his years.

In an insert between stories in the first issue, Bradbury writes, “I think Technocracy combines all of the hopes and dreams of science-fiction. We’ve been dreaming about it for years—now, in a short time it may become reality.” The concept of a technocracy drove so much of his fiction, including Fahrenheit 451. The transformation of dreams into reality, and the slipping of reality into dreams, marks nearly every Bradbury work I can think of, as well as what it means to be human. That he understood this at age 18, or at least strove to, might seem surprising, but makes all the sense in the world. Whatever it was that truly made him who he was, was there from the start.