The More Human Driverless Cars Seem, The More We Trust Them

This article is more than 2 years old

A recent poll conducted by PEW indicates that 50% of respondents would not ride in a driverless car. Living in Boston, I can say that I don’t really think driverless cars can be any worse than Boston drivers, although at the same time I don’t know that I’d trust a driverless car to navigate the insanity on the roads around here. Still, despite the apparent skepticism regarding this new technology, Google is busy testing theirs in California, Swedish researchers are conducting experiments on various autonomous driver systems, and professors in Chicago are researching ways to make them more trustworthy.

A recent poll conducted by PEW indicates that 50% of respondents would not ride in a driverless car. Living in Boston, I can say that I don’t really think driverless cars can be any worse than Boston drivers, although at the same time I don’t know that I’d trust a driverless car to navigate the insanity on the roads around here. Still, despite the apparent skepticism regarding this new technology, Google is busy testing theirs in California, Swedish researchers are conducting experiments on various autonomous driver systems, and professors in Chicago are researching ways to make them more trustworthy.

I haven’t driven in California, so I can’t compare the traffic to that on the East Coast, but however busy it is, Google isn’t deterred. The monolithic company conducted tests in Mountain View, where human drivers identified as many different traffic situations as possible to help develop software to help the cars respond. Driverless cars have to be able to react to everything from blinking traffic lights to the jerks that run red lights, but bit-by-bit, they’re figuring out how to enable cars to navigate city streets, which have more pitfalls than highways. Right now, the software distinguishes between pedestrians, cars, buses, cyclists, and crossing guards with signs—it even registers information from these various inputs simultaneously. So far, the cars have logged 700,000 miles on their own.

One of the downsides of built-in features designed to keep passengers safe, such as antilock brakes or even airbags, is that humans put too much trust in them and don’t drive as carefully. Manufacturers of driverless cars are considering that degree of faith and how that should impact their new products. Researchers at Sweden’s Lund University and the Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute studied systems such as adaptive cruise control, which allows a car to continue moving at a set speed, but then adapts if it notices the car creeping up on someone’s tail. Studies show that drivers trust this kind of device much more than a similar one that also allows a car to automatically follow another car, and change lanes when the other vehicle does.

One of the downsides of built-in features designed to keep passengers safe, such as antilock brakes or even airbags, is that humans put too much trust in them and don’t drive as carefully. Manufacturers of driverless cars are considering that degree of faith and how that should impact their new products. Researchers at Sweden’s Lund University and the Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute studied systems such as adaptive cruise control, which allows a car to continue moving at a set speed, but then adapts if it notices the car creeping up on someone’s tail. Studies show that drivers trust this kind of device much more than a similar one that also allows a car to automatically follow another car, and change lanes when the other vehicle does.

Their studies indicate that just because drivers believes in one system doesn’t mean they necessarily trust the others. This research also reveals that the more difficult a system is to turn off, the more drivers would allow it to navigate routine driving situations, but go to greater lengths to disable it in thornier driving situations. Essentially, the nature of decision-making during the act of driving is changing, but the results inspire hope in terms of people adjusting accordingly.

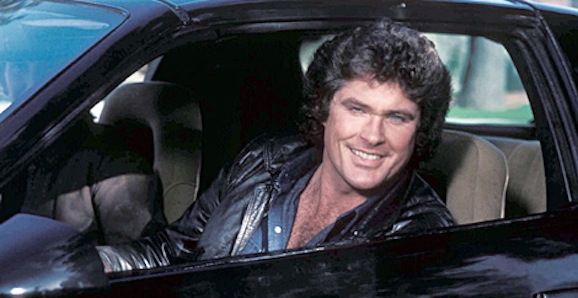

Another way people are adjusting their driving habits to include automated systems is by registering a preference for cars that behave like humans. I don’t mean giving other drivers the finger or honking incessantly for no reason, but rather, personifying the car. A study conducted by professors from the University of Chicago, Connecticut, and Northwestern found that giving a car a name made people trust it more. In the study, the car was named Iris, and it had a female voice (though probably not quite as alluring as ScarJo’s in Her).

Participants used a driving simulator that was either a conventional car, a car that autonomously controlled steering and speed, or a similar autonomous vehicle with a name, gender, and voice. The results revealed that the more human-like features the driving simulator had, the more participants trusted it. “Technology appears better able to perform its intended design when it seems to have a humanlike mind,” which will likely the designs of these cars in the future. Just think about how unstoppable Knight Rider would have been if KITT had sounded like a woman?