The Black Hole: Why Disney’s 1979 Sci-Fi Movie Failed And How It Nearly Worked

The best parts of The Black Hole are the flourishes of straight-up weirdness.

This article is more than 2 years old

For every box-office-topping mega-hit that opens in theaters, takes over the world, makes all the money, and wins all the critical acclaim, there are even more that don’t. That’s not always reflective of quality, however. Often times a movie falls through the cracks only to find an audience or critical reassessment later. Think Blade Runner or The Thing, which flopped and were panned on their initial releases, but are now heralded as genre masterpieces. Such is the case with Disney’s 1979 sci-fi adventure The Black Hole. Well, kind of.

Okay, the Mouse House’s attempt at space opera hasn’t received the same type of reevaluation as others. And if we’re being honest, it’s not even in the same stratosphere as those films mentioned earlier. Not by a long shot. Still, even with major problems and a mismatched mishmash of tones, there’s a lot to enjoy.

Cards on the table, I’m biased on this front. I saw The Black Hole at a young, formative age and have had an affection for it most of my life. Don’t worry, I recognize the flaws and won’t claim it’s an unimpeachable magnum opus, but it’s also still pretty fun, despite some rough patches.

A few scant years after Star Wars, The Black Hole is obviously Disney’s attempt to cash in on that market. I guess if you can’t beat them, buy them decades later for billions of dollars. It definitely doesn’t succeed on that front, and that’s a big part of the problem.

Star Wars came out and thrilled audiences, young and old. There’s something for everyone, adults and kids. The Black Hole shoots for that same broad appeal, only to miss the mark. Director Gary Nelson and writers Gerry Day and Jeb Rosenbrook try to explore dark, heady topics. It touches on philosophical arguments about boundary-pushing science and ethics in artificial intelligence; it talks about hard science, like event horizons, Einstein-Rosen bridges, and the nature of black holes. It’s often violent and grim. Hell, an evil robot saws Anthony Perkins to death and the main antagonist turns people into the equivalent of creepy space zombies.

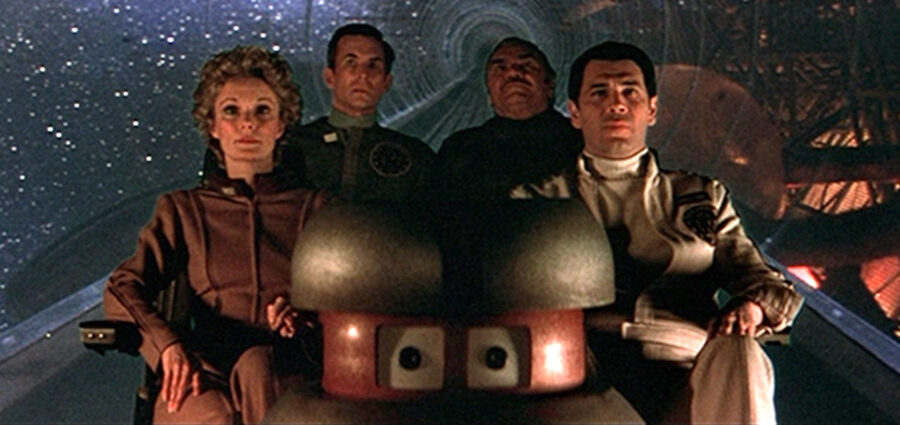

While the story about the crew of the Palomino (a deep-space research vessel that finds a long-lost scientific craft commanded by a mad scientist hovering at the edge of a black hole) plays out like melodrama draped in sci-fi trappings, it also injects cutesy flourishes aimed to placate kids. Particularly the robot VINCENT (Vital Information Necessary CENTralized) voiced by Roddy McDowall. He’s basically a floating keg painted in a way that looks like a South Park character. Or what about BOB (BiO-sanitation Battalion), his older, more beat up counterpart. Voiced by Slim Pickens, he’s the over-the-top hillbilly version. At best they come across similar to Twiki from Buck Rogers in the 25th Century.

While Star Wars balances these disparate elements, The Black Hole does not handle it well. The two tones—the dark and serious and the light and goofy—never mesh and the transition from one to the next is jarring, to say the least.

The film does have a great cast. At least on paper, because they’re not particularly good here. A roster that includes Anthony Perkins, Robert Forster, and Ernest Borgnine, as well as Yvette Mimieux and Joseph Bottoms, should be fantastic, right? Unfortunately, they’re not. Everyone is flat and bland and doesn’t appear particularly interested. The acting is more on par with a hurried, slapdash episode of some long-forgotten sci-fi series than a major studio offering.

Except for Maximilian Schell. He plays Dr. Hans Reinhardt, the captain of the USS Cygnus, the scientific vessel thought lost for 20 years. I remember being creeped the hell out by him as a child, and this latest revisit did not disappoint. First off, he looks like a lunatic with a shaggy mop of hair on his head and a near-Unabomber level of unkempt beard. He looks a little like Toecutter from Mad Max. A brilliant scientist, he’s unnerving and maniacal and chews every line in a perfect campy villain way.

It’s not entirely the fault of the cast—though Bottoms may or may not be a sentient block of wood—but the script bogs down in dialogue-heavy scenes that slow the pace and bloat the picture. Threads go nowhere, like early nods to an ESP bond between VINCENT and Dr. McCrae (Mimieux). The plot hits all the beats but never manufactures any viable tension or bond between the audience and the characters. Though life and death hang in the balance, you never feel the stakes. Even the action adds little to the proceedings. Stiff, near-unmoving robots stand still in a row and wait to be picked off one by one by our poorly aiming heroes.

Okay, I know I’m supposed to be defending The Black Hole. I plan to, I just wanted to get some gripes out of the way first.

The Black Hole was, at the time, the most expensive movie Disney ever produced. Which seems insane considering the budget was a reported $20 million and their latest space opera, Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker, cost more than ten times that. Different times.

As a result, the movie looks incredible. Sure some bits are dated, but the miniature work is top-notch and Disney pioneered techniques to composite live-action shots with matte paintings and computer work. Even zero-gravity scenes of the actors floating around still look pretty good, especially considering the age. Cinematographer Frank Phillips shoots sets with a flair of grandeur, one enhanced by an occasionally Victorian set design. Both Phillips and the special effects team received Academy Award nominations in their respective fields.

Though the wardrobes are questionable—the general style is best described as space sweatsuit chic—the robot design is cool and eerie. Yes, VINCENT and BOB look silly and like floating kegs, but Reinhardt’s various humanoid automatons skew toward the creepier side. Again, they owe a debt Star Wars, but with their own spin. Soldier bots are practically reptilian, and one particular hooded, reflective-faced android is especially spooky. They’re even more so when the big reveal happens and we learn their true nature.

The evil robot Maximilian, Reinhardt’s right hand, is easily the best of the bunch. Even without features to move or ways to emote, he exudes an air of menace and dread and is basically the Devil. The spinning saw blade hands don’t hurt matters. He’s uncanny and sinister and one of the enduring images from the film.

While occasionally tedious and overlong, the best parts of The Black Hole are the flourishes of straight-up weirdness. There’s a robot funeral and religious rites, uncanny automatons of various stripes, an unhinged mad scientist hell-bent on diving headfirst into a black hole, and things we’ve already mentioned, like a hillbilly robot.

Though these touches litter the film, The Black Hole never fully embraces its own strangeness, instead opting to play it safe. At least until the end, when it goes fully bug-nuts crazy in a way that, while it isn’t entirely earned, is certainly a hell of a lot of fun.

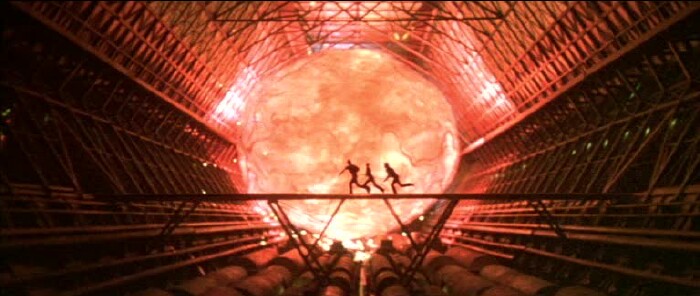

When the surviving crew members think they’re about to escape in a probe ship, they’re in for a rude awakening. Turns out the controls are programmed to take the craft into the heart of the black hole, where things veer toward the psychedelic.

First, we see Reinhardt and Maximilian become one, and the last we see of them is Maximilian standing atop a mountain, arms raised above an ocean of raging flames and hordes of black-robed creatures that look like the robots from the Cygnus. For the crew, instead of descending into hell, they pass through a crystal tunnel and come out in what is essentially heaven. It’s all very drugs.

Though they’re aping Star Wars and classic ‘70s disaster movies in large part, The Black Hole calls to mind two other films, one from before and one from after. It plays like a take on 2001: A Space Odyssey, maybe a watered-down version or 2001 for kids. It shoots for similarly obtuse ideas and goals, especially with the hallucinatory heaven-and-hell ending, though without the intellect or leg work to back any of it up.

The other is Paul W.S. Anderson’s 1997 sci-fi horror film Event Horizon. The two movies move in many parallel ways. Both revolve around a ship encountering a vessel thought long lost, both invoke Dante, things are not as they initially appear, paranoia and betrayal run wild, and in the end, they wind up in hell.

Even beyond that, there are similarities. Event Horizon has a moody, gothic aura; the ships resemble baroque castles. Early on, The Black Hole takes on a similar aesthetic—the ship design color palates create a near-medieval sensation, especially when the crew of the Palomino first encounters the Cygnus, unlit and appearing dead in space.

All things considered, it’s not hard to imagine why The Black Hole has a 40% score on review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, nor why the audience score is only 45%. As ambitious as it is, it’s deeply flawed. Too obtuse and slow for kids and too cutesy for adults, it doesn’t have a defined audience. It’s never going to be hailed as a masterwork or embraced as a cult classic, there’s enough weirdness and underlying strangeness that there will always be those of us who sing its praises.