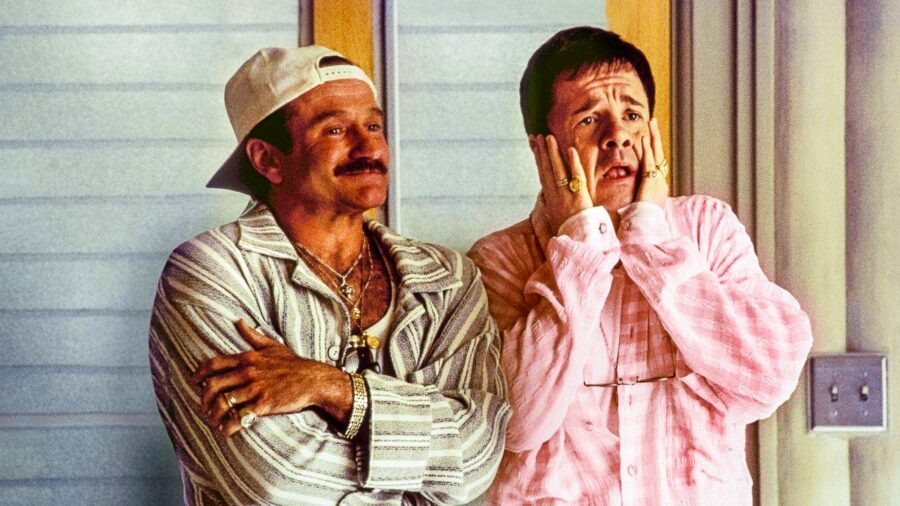

Robin Williams’ Best Movie Risked Getting Him Canceled

Robin Williams' best movie probably would get him canceled today, but it's a film with a deeply warm love for its characters.

This article is more than 2 years old

Over the course of his brilliant, prolific, and yet still too short career, Robin Williams managed to play in any number of genres. He could do drama, like his turn as an inspirational, desk-ruining English teacher in Dead Poets Society. He could do psychological thrillers, turning in unnerving performances as an obsessive photo technician in One Hour Photo and an Alaskan serial murderer in Insomnia. He could even play Peter Pan in whatever genre you want to consider Hook (though it is definitely not a musical). But above all else, Williams is remembered for his comedies. And while the popular (and to be fair, deserved) image of Williams’ comedic style was his prediliction for manic, rapid-fire referencing, imitations, and improvisation, his best comedy was in a different style: the farce. That movie is 1996’s The Birdcage.

The Birdcage was based on a French film called La Cage aux Folles, which itself was based on a 1973 play of the same name. Like all farces, it depends on misunderstanding and confusion for its humor, and there are few films that do it quite like The Birdcage. You know how you see a scene in a movie or sitcom in which someone rushes into a room, realizes they’ve made a mistake, and then rushes back out? That’s The Birdcage (and Robin Williams) in a nutshell, amped up to a thousand. And while the farce might not have the finest reputation as a comedic form, at its best, it is a kind of a comedic Rube Goldberg machine, where all the pieces are laid out from the beginning and then just gain more and more momentum as they go along. Fortunately, The Birdcage is actually the best.

And that should be no surprise. The Birdcage is absurdly stacked with talent on every level. Along with Robin Williams at the height of his comedic powers and popularity, there is Broadway legend Nathan Lane. There is Gene Hackman, turning his innate gravitas to buffoonery. There is two-time Academy Award winner Dianne Wiest, The Simpsons voice legend Dan Azaria, a pre-Ally McBeal Calista Flockhart, and multiple Tony Award winner Christine Baranski. Its glitzy, neon version of South Beach, Miami, was shot by legendary cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, who would go on to win Oscars three years in a row for Gravity, Birdman, and The Revenant. All this, and not to mention, the film reunited director Mike Nichols and screenwriter Elaine May decades after their legendary comic duo had abruptly been disbanded by May. When the two people who essentially revolutionized live comedy as we know it get back together for Robin Williams, that is a marker of quality. Heck, they got Stephen Sondheim to throw in a few songs for them, just because they could.

But The Birdcage could have been a disaster. At heart, the movie is a gay panic comedy, and those definitely do not age well. Looking back at gay representation on TV and film in the 1990s is a good way to ruin your childhood memories, trafficking as it so often did with cheap jokes, offensive stereotypes, and casual homophobia. The Birdcage manages to thread that needle, miraculously. The basic plot is as follows. Boy meets girl. Boy and girl fall in love. Boy and girl want to get married, but boy’s parents are proudly, openly gay, and own a drag club in South Beach, while girl’s parents are an ultra-conservative Republic senator adjacent to a sex scandal and a straight-laced housewife. Boy and girl hatch a plan to pretend boy’s parents are a straight couple (and a cultural diplomat to Greece), while girl’s parents are pursued by paparazzi. It’s pretty much one of the five fundamental story archetypes.

Yes, the essence of farce is misunderstanding and desperation, and it shows in The Birdcage. Every plan made by every person in the movie is perpetually at the brink of falling apart, and the level of flop sweat could keep the Titanic afloat. But whereas many farces are essentially cruel or deal with awful people, The Birdcage cares about its characters and how they are seen. Robin William’s Armand is a flamboyantly gay man perpetually dressed in loud Hawaiin shirts, but he is not a stereotype. He is a caring and responsible man who puts the needs of others before himself, even when it causes him pain. Nathan Lane’s Albert is a loud and frequently histronic drag queen, but he is portrayed with dignity and self-respect. The two are shown to have a loving, deep relationship that flew in the face of popular stereotypes of the LGBTQ+ image at the time. The warmth of The Birdcage is its secret and greatest weapon, showing that even a farce does not need to traffic in cruel labels or easy jokes. It was an enormous commercial success and well-received critically, and still has a sterling reputation as one of the finest movies of its genre. Also, it has Hank Azaria being unable to walk while wearing any kind of shoes, so you know it’s still a comedy.