The Zero Theorem: Christoph Waltz Brilliantly Seeks Meaning In Nothingness

It all adds up to something wonderful.

This article is more than 2 years old

“Be vewy, vewy quiet. We’re hunting entities.”

“Be vewy, vewy quiet. We’re hunting entities.”

Back in 1983, Terry Gilliam and his Monty Python cohorts took on the Meaning of Life, never quite putting a definition to it other than demonstrating that our lives are the sum of our experiences. Gilliam’s latest candy-colored mindbender, The Zero Theorem, is a film about a man who is also looking for a deeper context to this thing called existence. In narrowing his scope to one character, more or less, Gilliam is able to tackle vastly large ideas without having to pretend that he has all the answers. There is always meaning if you look for it. And if you don’t, well, that sure is some pretty scenery, isn’t it, Ma?

A hairless Christoph Waltz plays Qohen Leth, a computer programmer (for lack of a better job description) whose list of phobias, ticks, and eccentricities could fill a medical text. He lives the bulk of his solitude in a converted church where rats and birds are his unofficial roommates, only traveling outside to go to work for a company called Mancom that deals in crunching entities and liquid memory and other buzzwords that aren’t the point. Qohen’s main goals involve working from home and staying around his telephone, waiting for a magical call in which all of life’s mysteries will be revealed.

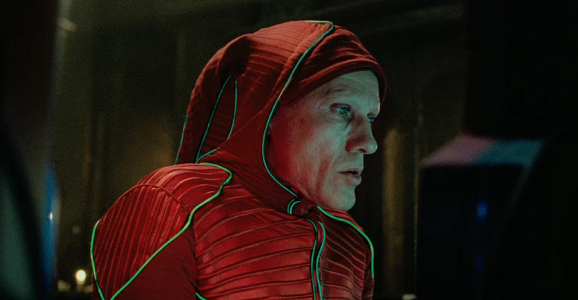

Qohen is good at his unintelligible career, and that’s recognized by Mancom’s head honcho, Management (Matt Damon), a Big Brother-ish personification of a demigod seeking an answer to the titular Zero Theorem. Though Damon is only on screen for a few minutes, the Management character is a constant presence throughout the film, always watching and manipulating things behind the scenes. Plus, his wardrobe is one of the film’s greatest achievements.

Though Qohen would rather live his life alone in front of his computer, a string of other characters enter his personal space, all seemingly trying to help him reach one breakthrough or another. There’s his supervisor Joby (David Thewlis), a genial chap who generally wishes to keep Qohen on the path to salvation, despite never bothering to remember his correct name. Mélanie Thierry is excellent as Bainsley, a semi-femme fatale who opens Qohen’s eyes to a world of emotion that he hadn’t necessarily been looking for. Bob (Lucas Hedges) is a teen computer genius who finds potential in Qohen and attempts to crack his third-person manner of living. Finally, Tilda Swinton appears via computer screen as Dr. Shrink-Rom, Qohen’s mandated and ever-present therapist. Other bit parts are played by an itchy Peter Stormare, Sanjeev Bhaskar, and Ben Whishaw. And pay attention to the commercials playing on the endless digital screens lining the city streets, as you’ll see Rupert Friend, Robin Williams, Gwendoline Christie, and more.

To describe The Zero Theorem as anything other than “a Terry Gilliam movie” would be a disservice to the passion that went into it. Whether on a technical or storytelling level, this is a huge movie, filled with high-ceiling sets, retro-technical props, brilliant color schemes, dazzling costumes, depressing existentialism, and big performances. Stop the movie at any point and the image on the screen could probably stand alone as a work of art, given Gilliam’s penchant for askew angles and fish-eye lenses. Plus, the entire production is a testament to the director’s efficiency in squeezing every iota of worth from the dollar, as this flick was made for around $8.5 million despite looking like it cost 10 times that much.

Many people have compared this movie to Gilliam’s classic Brazil, but it felt completely different to me, as it was more about the cog’s own inner mechanics, rather than the outer machine swallowing everything up. There’s a recurring image of an all-encompassing black hole that serves as either Qohen’s dream life or his worst nightmare, and it’s as good of an example as any of Gilliam’s constant balance between the macro and the micro, taking big steps in small places. It won’t, or can’t, resonate with everyone, because not everyone is equipped to obsess over their station in life in such a way.

For me, though, The Zero Theorem was a singular treat from beginning to end, largely because Gilliam isn’t playing this as a deeply heady drama. There is darkness, to be sure, but it’s all wallpapered over with comedic surreality. Maybe we’re not supposed to find humor in Qohen having to get dressed up in a complicated virtual reality suit in order to feel a sexual connection with someone, but I can’t assume Gilliam would want it any other way. To me, the tone of the film is fully expressed in Qohen’s stance that just because he wants to be alone doesn’t mean that he’s lonely. We aren’t meant to feel sorry for Qohen, despite Waltz’s sympathetic performance.

Walking away from The Zero Theorem, I don’t feel that I know any more about myself or about the commercialized world around me, but I suddenly want to run out and get to know as many people as possible. Not only because my personal beliefs about life are tethered to connectivity and friendships, but because I’m hoping to run into a Bainsley or two before I succumb to the whims of eternal nothingness.

Find The Zero Theorem on VOD and iTunes now, or catch it in theaters starting on September 19.