TV Review: The Challenger Disaster Is A Surprisingly Compelling And Profound Docudrama

This article is more than 2 years old

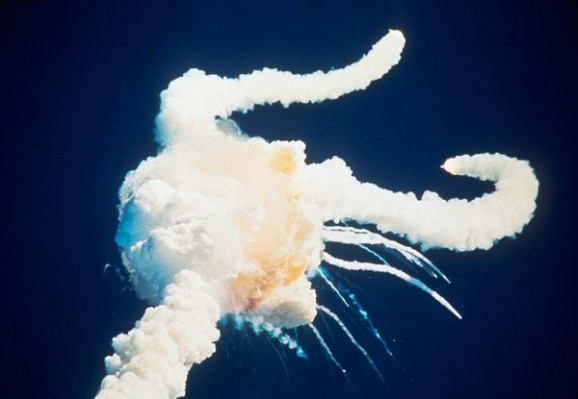

I remember January 28, 1986. I was seven years old. I, like so many other excited students, gathered in the cafeteria of my school just before lunch to watch the Challenger take off. I didn’t know a whole lot about space back then, except that it was far away, huge, and mysterious, and that those qualities also made it pretty cool. I had absorbed by then, though, that going into space was Important. It was one of those adventures that has and hopefully will continue to define humankind. I also knew that on board that ship was a teacher who also happened to be a woman. This brought the mission much closer to home for me, as it did for so many people. I remember watching the liftoff and clapping along with everyone else, even the folks in NASA’s control room.

But then, about a minute later, something really weird happened. At first I didn’t understand what was happening. Maybe space shuttles were supposed to do that — after all, there’s so much flame and smoke to begin with. It didn’t take long for all of us to realize that no, shuttles are not supposed to break into pieces and plummet back to Earth. I remember one of the teachers rushing over to the television and switching it off. The afternoon carried on just as it normally would, with lessons about subtraction and spelling. I don’t remember anyone at school offering much of an explanation — how could they? Not even NASA understood exactly what had happened — at least, not then. The teachers and administrators at school were fairly eager to sweep something that big and awful under the rug, or to let our parents deal with it. In retrospect, it occurs to me that the government tried to do the same thing.

That’s what The Challenger Disaster, a feature film developed by the Science Channel and the Discovery Channel and co-produced by the BBC, is all about. The film focuses on Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman’s work on the Presidential Commission investigating the cause of the shuttle’s failure. As the only independent member of that Commission, Feynman was in a uniquely objective position. Initially reluctant to join the Commission, in part because he was struggling with the cancer that would kill him two years later, Feynman eventually pursued the truth with abandon, threatening and pissing off loads of NASA and other public officials. Feynman is played by Academy Award winner William Hurt, who looks uncannily like Feynman in his older age and manages to pull off the somewhat eccentric but still credible genius with total believability. Brian Dennehy plays Presidential Commission Chairman and resident antagonist (when does Dennehy not play a dick?) William Rogers convincingly enough that I spent all but the last five minutes of the film wanting to punch him in the face. Neil Armstrong (Stephen Jennings) and Sally Ride (Eve Best) also show up in the movie, playing solid supporting roles, if only because of their celebrity status. The film is based on Feynman’s What Do You Care What Other People Think?: Further Adventures of a Curious Character, a book of essays, half of which are about his investigation into the Challenger disaster.

I was surprised at how riveting this movie was. The Challenger blows up before the five-minute mark — the rest is all investigation and inquiry. I don’t usually have a ton of patience for movies that seem to introduce obvious and predictable roadblocks to its protagonist’s obvious and predictable eventual victory, but I found it interesting how skeptical I became of NASA, an organization I tend to see as being victimized, or at least beaten back by the federal government, who currently allocates to the organization only half a penny of each dollar it doles out. To be honest, I didn’t know a whole lot about what actually did happen to the Challenger. I recall reading something about o-rings, but I just figured hey, you can’t make an omelet without breaking a few eggs. With an endeavor as insanely difficult and dangerous as manned space exploration, the odds are that something will go wrong eventually. The question here, though, is whether what did go wrong was foreseeable, and whether anyone actually foresaw it.

As it turns out, probabilities were one of Feynman’s specialties. Even though the shuttle had over 2.5 million parts — a fact that Rogers brings up in the Commission’s first meeting, and which leads him to plant this seed: “it may be after due consideration that it’s just not possible to identify the cause” — Feynman’s like, hey man, I can do crazy quantum physics and stuff, so your 2.5 million parts don’t scare me! But it’s disconcertingly clear from the get-go that Rogers is angling for an inconclusive finding. He starts the first meeting by telling the panel, “We are not going to conduct [the investigation] in a manner that is in any way unfairly critical of NASA. Because we believe, and certainly I believe, that NASA has done an excellent job. And I believe the American people think so too.” So, um, have fun in Washington and see you in a week!

This was a bit of a revelation for me, although in retrospect it shouldn’t have been. NASA is a government agency. I want to think of it as being immune from the foibles that dog every other part of the government, but it’s not. It’s important to remember, though, that Rogers wasn’t actually a member of NASA — he was a cabinet member (and former U.S. Attorney General and U.S. Secretary of State) appointed to head this commission, so it’s likely he was trying to portray NASA favorably, knowing that the outcome would reflect on the entire government. Various members of NASA were less than forthcoming about the truth for reasons that are understandable — they didn’t want to get their colleagues in trouble. But as Feynman points out, without the truth, they were all eventually out of jobs anyway. Feynman got a few anonymous tips and hints along the way, in addition to some non-anonymous but still cryptic nudges in certain directions.

All the while, Feynman has to deal with not one, but two types of cancer, both of which were relatively rare on their own and practically unheard of together. There’s a moment in the film in which Feynman reflects on the possibility that his cancer was caused by exposure to radiation while working on the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos to develop the atomic bomb before the Nazis did. He mentioned watching the Trinity bomb test with only a pair of glasses as protection. This moment could have easily been hamfisted, but it wasn’t. Feynman got excited when recounting his work in those days, and it’s clear he didn’t regret it. It wasn’t played in a “science can kill you” way, which was a good call given that the entire movie could have been spun that way. Rather, Feynman’s contemplation on his rapidly approaching death mirrors the deaths of the astronauts, and the movie depicts them all as people devoted to science to the extent that they would — and did — die for it. Their deaths really aren’t all that different and Feynman knew it, which is part of why he worked so hard to uncover the truth about what really happened.

I won’t give away all the details about the ending of the movie, even though some of you already know how it turns out. Suffice it to say that Feynman eventually made his case and the Commission’s final report, which was presented to President Reagan, included his appendix, “Personal Observations on the Reliability of the Shuttle.” Even though he wasn’t an astronomer, Feynman was a scientist who pursued the truth until the bitter end. And the movie works because no cinematographic or directorial tricks got in the way — they weren’t necessary. The film is a refreshingly and relatively rare example of how an important story can tell itself.

I can see people not wanting to watch the Challenger Disaster because it forces viewers to reckon with and revisit that day and its implications, but I think this film is important. It explores the pressures put on a government to deliver not just a successful mission, but a fast one. The weather was particularly cold that January morning, and it turns out that delaying the launch might have made all the difference. But delays are problematic — people start worrying that a delay means lack of confidence in the mission, and the government is invested in adhering to timetables for reasons that will never be entirely transparent to us. I thought about that today as I watched the Mars MAVEN take off, and I’ll think about it each time I see a spacecraft launch. If this movie does one thing, it’s to underscore the importance of one of Carl Sagan’s most profound messages:

Because science carries us toward an understanding of how the world is, rather than how we would wish it to be, its findings may not in all cases by immediately comprehensible or satisfying…there are no forbidden questions in science, no matters too sensitive or delicate to be probed, no sacred truths.