Help Researchers Figure Out How To Help Robots Understand Your Commands

This article is more than 2 years old

While significant strides have been made recently in natural language processing, one of the current drawbacks for most robots is the inability to understand language that isn’t coded in ones and zeroes. For programmers, a future full of robotic servants, coworkers, and mates might seem pretty exciting, but for those of us who would rely on spoken language to communicate with robots, it seems a little more daunting. Cornell’s Robot Learning Lab is hard at work on this problem, trying to teach robots to take verbal instructions.

While significant strides have been made recently in natural language processing, one of the current drawbacks for most robots is the inability to understand language that isn’t coded in ones and zeroes. For programmers, a future full of robotic servants, coworkers, and mates might seem pretty exciting, but for those of us who would rely on spoken language to communicate with robots, it seems a little more daunting. Cornell’s Robot Learning Lab is hard at work on this problem, trying to teach robots to take verbal instructions.

Language itself is often vague and broad — take Isaac Asimov’s three laws of robotics, for instance. The first law is that a robot cannot harm a human, or allow a human to come to harm. At first glance, that might seem clear enough, but what exactly constitutes harm? Asimov himself posed this question in the story “Liar!” which features a mind-reading robot named Herbie. Herbie lies to its human colleagues because it knows what they want it to say — he tells an ambitious human that he’s next in line for a big promotion, and he tells a heartsick human that her feelings for her coworker are reciprocated. Herbie lies because telling people what they don’t want to hear would be emotionally harmful, but of course when they realize Herbie has been lying they’re humiliated and undergo harm anyway. Asimov’s law is typically interpreted as intending to prevent physical harm, but Herbie’s read of the law makes sense, given the different types of harm one can experience. If a robot were to be programmed with such a law, the robot would also have to be programmed with an understanding of all the different interpretations of the word harm, as well as relative harm (a scratch versus a bullet wound, etc).

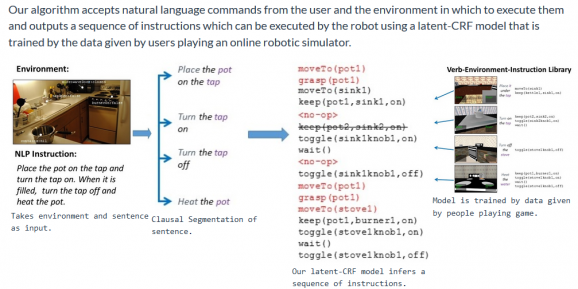

Researcher Ashutosh Saxena is trying to figure out a way to help robots deal with linguistic ambiguities, largely by applying knowledge of the environment to the situation. Robots’ lack of experience only exacerbates the language gap — I could tell a robot to turn the channel to the World Cup match, but if I haven’t told it to turn the television on, it’s not going to be of much help. Saxena’s research involves using a camera that helps the robot figure out where it is and what other objects and people are around, so it can use that information to help guide its actions — essentially, the camera is intended to provide context for the robot, which in turn can help it better understand and carry out instructions.

Saxena’s robots would already have been exposed to video simulations of similar actions and have stored that data. So when a person asks the robot to do something, it searches its databank for a similar scenario and tries to figure out not just how to carry out the command, but how to best carry it out depending on the situation. Saxena’s research is promising — the robots can follow instructions 64% of the time, including varied and somewhat more complex instructions. Right now, he’s building a library of various instructions that a robot might receive in a kitchen — the more instructions in the database, the better the robots can perform. You can help develop robots’ repertoires by communicating with a robot simulation at Cornell’s website, “Tell Me Dave.”