Political Beliefs Decrease Our Ability To Reason

This article is more than 2 years old

I’ve spent a lot of time in the past week (and in the past couple decades) trying to understand politics. While I recognize the various strategies in play, on a basic level I don’t understand what the hell is wrong with our government, and why our politicians seem to be devoid of, or intentionally quashing, their ability to be reasonable. I also don’t understand how voters can be so dangerously ignorant. The most recent troubling example is the CNBC poll that reveals the staggering number of people who don’t know what ObamaCare and the Affordable Care Act are, and who don’t realize that they’re the same law. Regardless of one’s political leanings, for me it all boils down to one question: why can’t politics and reason coexist?

I’ve spent a lot of time in the past week (and in the past couple decades) trying to understand politics. While I recognize the various strategies in play, on a basic level I don’t understand what the hell is wrong with our government, and why our politicians seem to be devoid of, or intentionally quashing, their ability to be reasonable. I also don’t understand how voters can be so dangerously ignorant. The most recent troubling example is the CNBC poll that reveals the staggering number of people who don’t know what ObamaCare and the Affordable Care Act are, and who don’t realize that they’re the same law. Regardless of one’s political leanings, for me it all boils down to one question: why can’t politics and reason coexist?

I didn’t expect science to uncover the answer, though, in retrospect, I shouldn’t be surprised. Yale law school professor Dan Kahan’s paper, “Motivated Numeracy and Enlightened Self-Government,” explains what I’ve spent my entire life not understanding. His study shows that people are bad at solving problems if the answer seems to compromise their political beliefs. This doesn’t just apply to societal, economic, or political problems — this applies to straightforward, objective math problems, which signifies just how deeply ingrained our stubbornness is, and sheds new light on what we perceive as ignorance.

Kahan and his colleagues devised a pretty smart study, for which they had 1,111 participants. I’m not sure why they didn’t just go with 1,000, as that makes the math easier, but I’ve never claimed to be good at math (and now I wonder what this says about my politics). Anyway, the subjects were initially surveyed about their political leanings, as well as given a basic set of questions to determine their ability to reason mathematically. This is how Kahan was able to determine a baseline in terms of the participants’ basic beliefs and aptitudes.

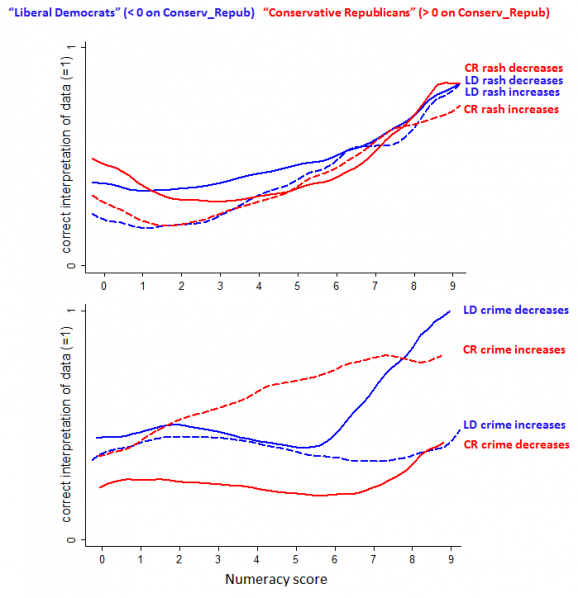

Then came the fun part — he gave them some mathematical problems that required them to interpret the results of a fake scientific study. The concocted study was sometimes presented to the subjects as data on the efficacy of a skin cream, and other times, the study was said to gauge the efficacy of a ban on concealed handguns. The trick was that the numbers were exactly the same — thus, the conclusions participants drew based on the math should have been the same. But they weren’t.

Respondents had very different answers to the same math problem depending on whether they were told the fake study involved skin cream or guns. Even more surprising is that both liberals and conservatives who are particularly adept at mathematical reasoning are more likely to let their political leanings affect their thought process than people who aren’t as good at math. Hey, there’s an upside at being crappy at math, no?

In case you were wondering, in the skin cream scenario, the ratio of people whose rash improved vs. those for whom it got worse was 3:1, while for those who didn’t use the cream, it’s 5:1, suggesting that the cream isn’t effective (unless you like a bad rash). Kahan also reversed the data for half of the participants, in which case the conclusion would be the exact opposite. If you’re like me, you’re thinking that the actual math problem isn’t easy in the first place — to get the right answer you have to figure out the ratios, rather than simply comparing numbers. 59% of respondents in the study got the wrong answer, which makes me feel a little better.

Participants who initially tested as particularly numerate, or good at mathematical reasoning, were more likely to get the skin cream answer right regardless of political affiliation. But when the problem dealt with guns, nearly all numerate Democrats got the answer right when the right answer was that the weapons ban worked. But when the numbers were reversed, indicating that the ban didn’t work, they didn’t do nearly as well. The same applied to the Republicans — they got the problem right when the correct answer suggested an ineffective gun law, but didn’t do well when the correct answer contradicted their basic anti-gun control stance.

In science, there’s something called a deficit model, which suggests that if people had more knowledge or a better ability to reason, they’d be more likely to agree with scientists about climate change, vaccinations, and other issues that rely on data. Kahan’s study shows the exact opposite — that knowledge or reasoning ability isn’t really the issue, and that political beliefs are.

Kahan believes that when the numerate subjects intuited that their initial answer might be wrong (which generally tended to be the case if they compared numbers and jumped to the more obvious conclusion), they worked harder to figure out the right answer. But if they determined that the right answer contradicted their views, they worked harder still to find another way to figure it out. In a nutshell, that means people perform well when their reasoning supports their political beliefs, but tend to have a blind spot if it doesn’t. Kahan also thinks that many participants simply chose the answer that initially seemed right, so long as it was consistent with their beliefs.

The study confirms what we all know, but often forget: we’re all fallible. No one is devoid of prejudice or subjectivity, no matter how hard one might try. Accepting this fact and realizing that it may affect the way we perceive and reason is important to our ability both as individuals and as a society to compromise, to empathize, and ultimately, to solve problems. I’d love for Kahan to take this study to Capitol Hill, but I think we already know how that would go.