Nanoparticles Loaded With Bee Venom Could Help Prevent HIV Infection

This article is more than 2 years old

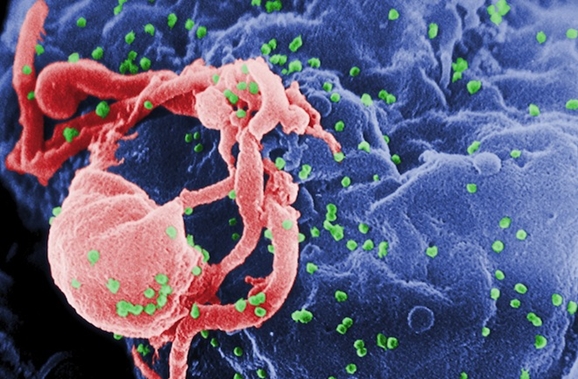

Scientists have taken an important step in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) research. A team at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis has found a way to eradicate HIV while leaving surrounding normal cells unscathed. It involves nanoparticles carrying a toxin found in bee venom. The researchers hope to develop this technique to create a new vaginal gel that will prevent the spread of HIV, the virus that causes AIDS.

Joshua L. Hood, MD, PhD, a research instructor in medicine at the Washington University School of Medicine, feels this could be the best way to prevent HIV and destroy the virus before it develops into AIDS. “Our hope is that in places where HIV is running rampant, people could use this gel as a preventive measure to stop the initial infection,” Hood says.

Melittin is a potent toxin found in bee venom, and it would be used to poke holes in the protective layer that surrounds HIV and other viruses. According to researchers, a large amount of free melittin can cause significant damage to HIV’s protective envelope.

Hood contends that melittin injected into nanoparticles does very little harm to normal cells because he’s added special “bumpers” to the nanoparticle’s surface. The particles bounce off the bumpers, which are much larger than normal cells, but latch onto HIV, which is much smaller. When the HIV comes into contact with the nanoparticles, the deadly bee toxin will be waiting for it. “Melittin on the nanoparticles fuses with the viral envelope,” Hood says. “The melittin forms little pore-like attack complexes and ruptures the envelope, stripping it off the virus.”

The tricky part of the research is how to stop the HIV from replicating. While the nanoparticle attacks the viral envelope, the anti-replication strategy does very little to stop the initial infection, so some strains have found a way to reproduce, despite the new drugs.

“We are attacking an inherent physical property of HIV,” Hood says. “Theoretically, there isn’t any way for the virus to adapt to that. The virus has to have a protective coat, a double-layered membrane that covers the virus.”

While Hood and his team are developing this technique in the form of a preventive gel, they are also looking to introduce this new drug to people with HIV and would deliver it to them intravenously to clear the virus from their bloodstream.

The new study appears in the current issue of Antiviral Therapy.