New Malaria Vaccine Has A Successful Clinical Trial

This article is more than 2 years old

Last summer I traveled to the Choco region of Colombia, a remote area near the Pacific Ocean known for rainforests, drug trafficking, and wildlife, especially mosquitoes. Malaria-carrying mosquitoes, to be precise. Before I left, I had to be vaccinated against yellow fever, and because no such vaccine exists for malaria, I had to get a prescription of Malarone, the most effective, and least system-ravaging, preventative medication against the disease. Each of those little pills cost about $10 and I had to start taking them three days before entering Choco and a week after I left. Unlike other malaria medications, Malarone didn’t make me hallucinate, which sounds like a good thing, and the side effects were barely noticeable.

Last summer I traveled to the Choco region of Colombia, a remote area near the Pacific Ocean known for rainforests, drug trafficking, and wildlife, especially mosquitoes. Malaria-carrying mosquitoes, to be precise. Before I left, I had to be vaccinated against yellow fever, and because no such vaccine exists for malaria, I had to get a prescription of Malarone, the most effective, and least system-ravaging, preventative medication against the disease. Each of those little pills cost about $10 and I had to start taking them three days before entering Choco and a week after I left. Unlike other malaria medications, Malarone didn’t make me hallucinate, which sounds like a good thing, and the side effects were barely noticeable.

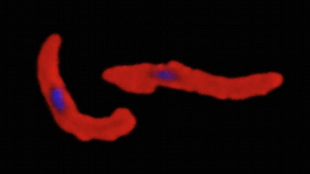

A year ago, it was by far the best option for someone going to a malaria-risk zone. Not anymore. Scientists at Sanaria, a Maryland biotech firm, have made a malaria vaccine called PfSPZ that has proven effective in protecting against the disease in a Phase I clinical trial. Like most vaccines, this new one uses a form of the disease for inoculation. You take infected mosquitoes and subject them to radiation, weakening the parasites. They then extracted the virus from the mosquitoes’ salivary glands, and then cryopreserved them.

40 of the 57 adults in the clinical trial were given doses of the vaccine. None of the patients had adverse reactions to the drug, and the ones given the highest dose had the best cell responses and antibody production. So far so good. Then came the fun part—foisting malaria-carrying mosquitoes on the subjects. I hope the National Institutes of Health paid subjects well for their participation, and not just in PfSPZ.

3 subjects of the 15 who received the highest dose of the medication became infected, while 16 of 17 of the participants who received a low dose became infected. 11 of the 12 control subjects (they received placebos instead of the vaccine) contracted the disease. In case you were wondering, the subjects who got the disease were treated with anti-malarial medication—probably good ol’ Malarone.

Malaria is one of those diseases you don’t want to mess around with. The first stage of infection involves chills, malaise, headache, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. And that’s just for starters. The second stage is a fever, which segues nicely into the third stage of sweating, weakness, extreme fatigue; possible liver, kidney, or spleen complications; and maybe a build-up of fluid in the lungs. It usually takes a few days after being bitten for people to develop these symptoms, but certain particularly virulent strains of malaria can kill mere hours after a mosquito bite. Certain types of malaria can cause death if untreated, while others are less serious but can produce symptoms that last for up to three years—the virus can survive, dormant, in the blood for years, even decades. It really sucks to get malaria.

And while Malarone was a bit of a pain in the ass, I have no misgivings about taking it. Next time, though, if the PfSPZ is available, I’ll go that route. There’s just one detail that gives me pause—instead of injecting the vaccine into the skin or tissue, as with most vaccinations, PfSPZ needs to be delivered intravenously to be effective.

The vaccine builds upon research done since the 1970s, when it was discovered that the bites of malaria-carrying mosquitoes offered some protection from the disease if the mosquitoes first underwent radiation. The next phase of the trial will be conducted in Tanzania, against African strains of the disease.