Fifteen-Year-Old Creates Flashlight Powered By Body Heat

This article is more than 2 years old

Last time I was in a science fair, I did an experiment about the effects of grow lights on plants. Shocking to absolutely no one, plants spending four to six hours a day under the lights grew more than plants that sat on the window. I was pretty jazzed about this project, though — any excuse to play scientist was a good one in my book.

Last time I was in a science fair, I did an experiment about the effects of grow lights on plants. Shocking to absolutely no one, plants spending four to six hours a day under the lights grew more than plants that sat on the window. I was pretty jazzed about this project, though — any excuse to play scientist was a good one in my book.

Times have changed.

Back when I grew those plants, I didn’t have a computer (yes, I’m a fossil), much less any other advanced technological gizmos. But now I’m making excuses for myself. Even if I entered a science fair today, I wouldn’t be able to do what Ann Makosinski, a tenth-grader from Victoria, British Columbia did. Makosinski invented a flashlight that operates via the heat of a hand.

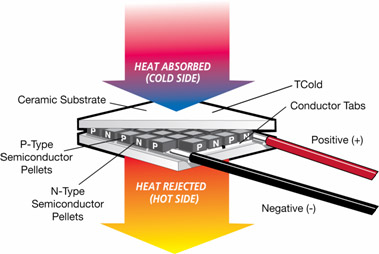

She wanted to figure out how to “harvest surplus energy” and eventually came up with the idea of using the thermal energy humans produce. To build a flashlight that turns on when grasped by a human hand, she used Peltier tiles, which produce electricity when one side is heated while the other side is cooled.

In Makosinski’s case, she used the heat of the human hand on one side and cooler ambient air on the other. This provided enough energy for an LED to produce light, but not enough voltage. So Makosinski set about solving the voltage problem by both buying and building circuits. Through trial and error, she redesigned the circuit and boosted the voltage with transformers, ultimately figuring out how to power the light with an input of less than 50 millivolts.

Then she had to design the flashlight itself. She used a hollow aluminum tube, which allowed the air to flow freely and cool one side of the Peltier tile. She also created a second flashlight using a standard PVC tube. The colder it is, the brighter the beam, due to the contrast between the temperature of the air and the body. But even in warmer temperatures, both flashlights produced steady light for over 20 minutes.

Her flashlight can produce 5 milliwatts of power and five “footcandles” of brightness, which is a nifty term that I will now adopt for measuring luminescence — one footcandle is the brightness of a light source at a distance of one foot. By comparison, the Mini Maglite LED flashlight, described as “scorchingly bright,” generates 84 lumens of visible light. Makosinski’s flashlight generates roughly 53. To put it technically, her flashlight is totally legit.

In case you were wondering, that same Maglite costs approximately $20, not including batteries. Makosinski made her flashlight for about $26, but if it were mass-produced, it would be considerably cheaper. Move over, Maglite.

So, how’d Makosinski do in her science fair? Better than me with my plants, that’s for sure. She is one of 15 students around the world to advance to the Google Science Fair finals. She’ll have to wait until September to get the results, but she’ll get to visit Google headquarters in California, where three winners in the three different age categories will be announced. One of them will win the grand prize — a $50,000 Google scholarship and a trip to the Galapagos. If only I could travel back in time and try harder in science!

Makosinski had her share of obstacles as she worked for months on this project, but sometimes, “you just kind of have to keep going,” especially when you have school plays and homework to do. Here’s hoping she gets to illuminate some wild nocturnal animals on Galapagos. Maybe she can invent a body-heat powered camera for the trip.